Table of Contents (click to expand)

While researchers have made strides in astronomy, finding exomoons has been difficult, but they seem to be making more progress in recent years.

One of the most exciting and sought-after fields in modern-day astronomy relates to exoplanets. Discovering and understanding planetary systems in other stars will help us learn more about the formation of the planets and moons of our own solar system.

Ever since the discovery of the first exoplanet in the 1990s, we have observed thousands of them through the use of reliable, indirect methods. The Kepler Space Telescope and Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) are well-known instruments used to observe exoplanets.

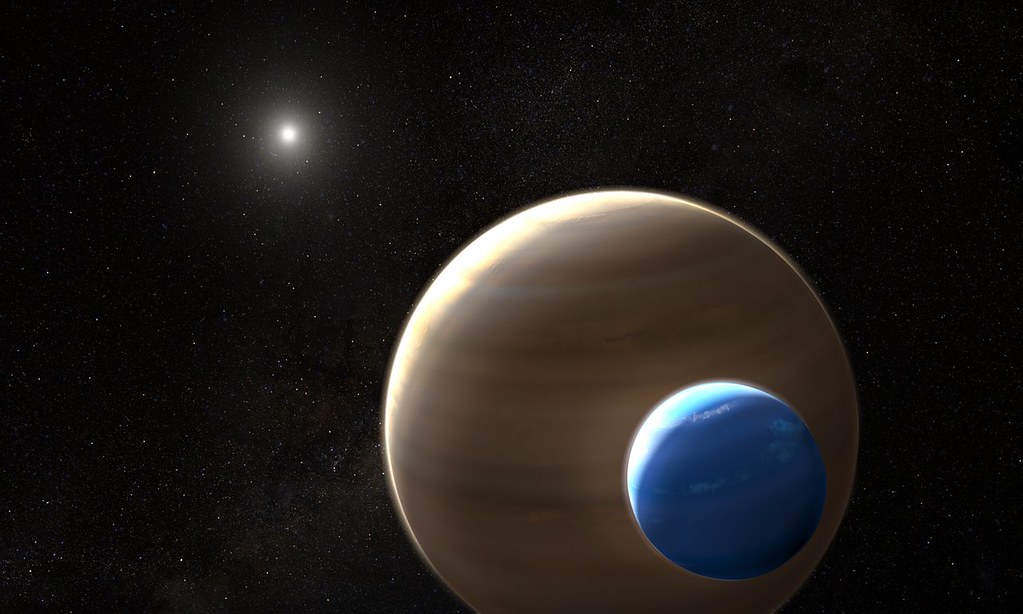

While exoplanets can be reliably detected using indirect methods, their moons, also called exomoons, are much more challenging to observe. While they do exist in theory, they’re much smaller than the parent planet they revolve around. They also only reflect the light coming from their star. For these reasons, exomoons are complicated to observe directly and confirm.

Despite that, astronomers and astrophysicists have suggested several methods for better detection. These detection methods consist of transit-timing variations (TTVs), direct imaging, signatures in transit spectra, and more. The confirmation of exomoons is very complicated, however, requiring more methods for their detection.

Recommended Video for you:

The Hunt For Exomoons With Kepler (HEK)

One of the most recognized searches for exomoons in astronomy is ‘The Hunt for Exomoons with Kepler (HEK).’ In this, scientists look for minute dimming of the starlight by the exomoon candidate and its parent exoplanet, using the data obtained from the Kepler Mission.

Here, they search for possible candidates using a technique called transit-timing variation. Minute changes in the transit time of the planet across the face of its parent star may indicate the presence of an exomoon.

The study also uses a statistical system called the Bayesian framework, which tests suitable candidates against planet-only and planet-with-moon models. It accounts for the fact that the variations in transit time can also occur due to other exoplanets within that star system, not just due to exomoons.

The HEK also tries to use a technique called radial velocity (RV) variations. In this, the method considers the wavelength of light emitted by the host star. While there will be alterations in the wavelength due to the exoplanet, exomoons might also create subtle changes. The RV method can also determine the size and mass of the planet-moon system. The intensity of the light wave can also remove any false positives.

The HEK project published its first paper in 2012, after which it published four more articles providing additional details. In their fifth article, published in 2017, they show evidence for an exomoon candidate revolving around an exoplanet in the Kepler-1625 star system. It also mentions a set of possible super-Ios. The project group, however, was uncertain about its significance and did not make any conclusions regarding it.

In March 2022, David Kipping, an American astronomer and one of the principal investigators of the HEK, analyzed the Kepler data. He examined a survey conducted of 70 gas giant exoplanets. From that survey, he found that one exoplanet, Kepler-1708 b, might possess an exomoon. Interestingly, both the candidate exomoons found in Kepler-1625 b and Kepler-1780 b have unusually high masses, comparable to Neptune.

David Kipping and his team continued to study the Kepler data for transit time variations. In November 2022, after a thorough analysis searching for any significance in the deviations and several statistical evaluations and reliability, they determined that the exoplanet Kepler-1513 b might contain an exomoon. However, they found that the exomoon mass predicted from the planetary models and the one obtained from the TTVs did not match. Thus, further observation was required.

Apart from the HEK, there are other research attempts to learn more about exomoons. One such research study involves understanding why the atmospheric spectrum of some exoplanets shows the presence of sodium and potassium gas.

Other Predictions/detection Methods

To understand the presence of such gases, scientists performed spectroscopic analysis and simulations based on density profiles. They deemed that the existence of an exomoon could be one reason for the sodium and potassium layers seen in the atmospheres of the exoplanets WASP-49 b and HD189733 b. However, the study also showed that the sodium and potassium gas could arise from within the exoplanet or from a toroidal ring of matter surrounding it.

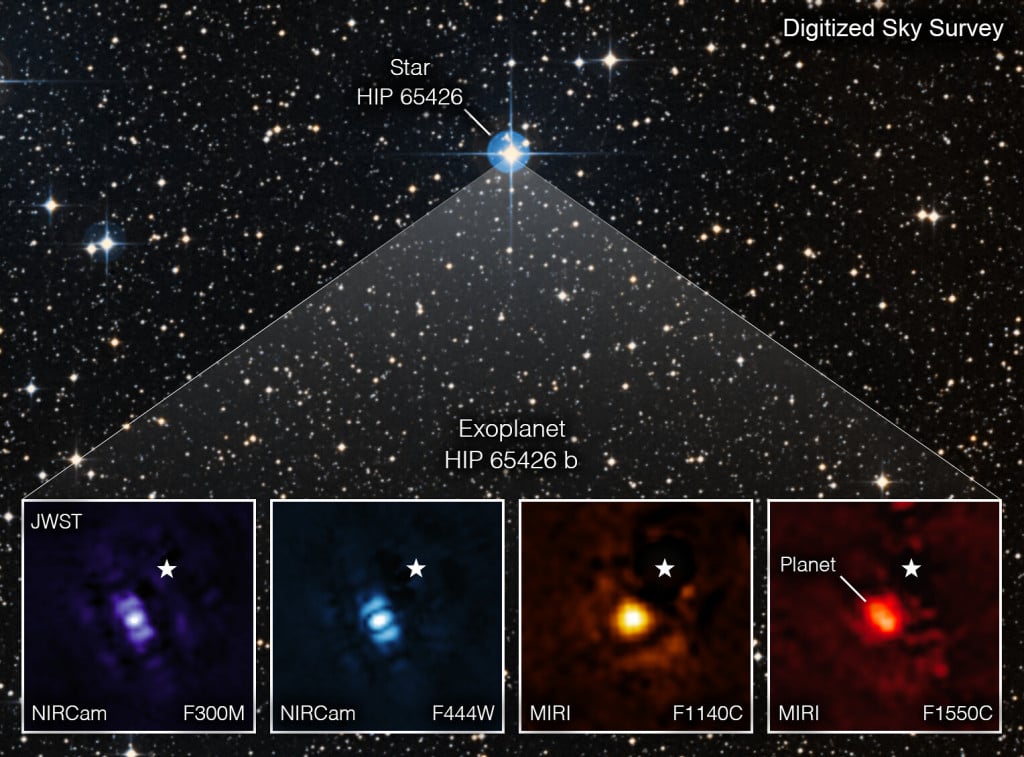

One proposed method for the detection of exomoons involves exoplanets that are isolated, located at faraway distances from stars. Such planets are called isolated planetary-mass objects (IPMOs). In such cases, exomoons can be detected from their transitions across the IMPOs. IPMOs appear to be sufficiently bright when observed in infrared. Astronomers have already found around 57 IPMOs. Using the James Webb Space Telescope, we expect 37 of them to show transitions of Ganymede or Titan-sized exomoons.

Former Exomoon Candidates

There has been a case where scientists thought that they had discovered exomoons, but have since found them highly improbable. In November 2020, astronomers studied 13 exoplanets discovered by the Kepler mission for transit time variations. Of the 13, 8 candidates indicated that they might contain an exomoon.

The candidate exomoons are found in the exoplanets: 1. Kepler-517 b; 2. Kepler-809 b; 3. Kepler-857 b; 4. Kepler-1000 b; 5. Kepler-409 b; 6. Kepler-1326 b; 7. Kepler-1442 b; and an eighth candidate that has no Kepler designation.

However, Kipping conducted an independent analysis of those eight objects. His investigation consisted of three tests to find these answers: 1. If there are any substantial detections in the TTVs; 2. If the TTVs are periodic; and 3. if the exomoons have a non-zero mass.

From the eight detected in November 2020, Kipping found that six were highly unlikely to contain exomoons. Two candidates (the undesignated one and Kepler-1442 b) failed all three tests, while another three (Kepler-517 b, Kepler-1000 b and Kepler-409 b) passed just one test each (not the same test individually).

The sixth candidate (Kepler-1326 b) passed two tests, only failing the periodicity test. Kipping explained this by stating that the TTVs could have originated due to some event in the parent star. Also, calculations show that the exomoon has a negative radius, making it unsuitable as an exomoon candidate.

Summary

It is challenging to find exomoons, let alone study them. To effectively determine their presence, we need many tests, and all of them should agree on quantities like their mass and radius. There is certainly a need to work out more methods for their detection. With current missions like JWST and future missions giving more precise data, we should have confirmed sightings of exomoons soon.

Discovering and studying exomoons could provide more clues on their formation and give us some hindsight on the creation of our own Moon. It would help us gain more knowledge on the evolution of star systems and planets, as well as their ultimate fate.

References (click to expand)

- Astronomers Have Found Another Possible 'Exomoon' beyond .... Scientific American

- Overview | What is an Exoplanet?. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration

- Kipping, D. M., Bakos, G. Á., Buchhave, L., Nesvorný, D., & Schmitt, A. (2012). The hunt for exomoons with Kepler (HEK). I. Description of a new observational project. The Astrophysical Journal, 750(2), 115.

- Teachey, A., Kipping, D. M., & Schmitt, A. R. (2017, December 21). HEK. VI. On the Dearth of Galilean Analogs inKepler, and the Exomoon Candidate Kepler-1625b I. The Astronomical Journal. American Astronomical Society.

- Kipping, D., Bryson, S., Burke, C., Christiansen, J., Hardegree-Ullman, K., Quarles, B., … Teachey, A. (2022, January 13). An exomoon survey of 70 cool giant exoplanets and the new candidate Kepler-1708 b-i. Nature Astronomy. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- D Kipping. search for transit timing variations within the exomoon corridor .... Oxford University Press

- Limbach, M. A., Vos, J. M., Winn, J. N., Heller, R., Mason, J. C., Schneider, A. C., & Dai, F. (2021, September 1). On the Detection of Exomoons Transiting Isolated Planetary-mass Objects. The Astrophysical Journal Letters. American Astronomical Society.

- (2020) Alkaline exospheres of exoplanet systems: evaporative .... Oxford University Press

- (2021) Exomoon candidates from transit timing variations: eight .... Oxford University Press

- Kipping, D. (2020, September 15). An Independent Analysis of the Six Recently Claimed Exomoon Candidates. The Astrophysical Journal. American Astronomical Society.