Table of Contents (click to expand)

Modern ships are built to withstand such movements, so unless you’re in the midst of turbulent weather, you won’t feel the movement of the ship.

The Earth is a pretty huge place. From crawling on all fours to bipedalism to the invention of the wheel, species have learned to deal with that undeniable fact. Nowadays, the general public has the means to traverse thousands of kilometers in a matter of hours, so we tend to take for granted the vast distances that separate us from the rest of the world. Before the advent of ships, cross-continental travel was mostly impossible.

In fact, there was no way for human beings from one continent to even know about the existence of the other continents.

Recommended Video for you:

Maritime Travel – An Overview

The earliest historical evidence of the existence of ships dates back to the 4th millennium BC[1], from the Egyptian civilization. The rest, as they say, is history. From a basic means of travel, ships have now become a status symbol. Cruise liners, yachts, onboard hotels, and massive transit ships are the culmination of the human need for travel and the human desire for comfort.

Just like any other mode of travel, ships have their own set of trade-offs. The primary one is the unpredictability of weather conditions and how that weather impacts the water bodies in question. Turbulent weather has been a hazard to overseas travel for as long as overseas travel has existed. Ships are built to withstand a certain degree of turbulent weather and weathering, just due to being in the water all the time, but there is no way of predicting the real-life conditions a ship will face with 100% accuracy.

However, to answer the original question, let’s disregard extreme conditions where a ship is facing a fate like the Titanic.

Ships have two uses, transporting cargo and transporting people across bodies of water. In either case, it is necessary to ensure that the ship protects its contents from external turbulence. Cargo, whether material or human, is precious and usually insured, so it must be protected from damage.

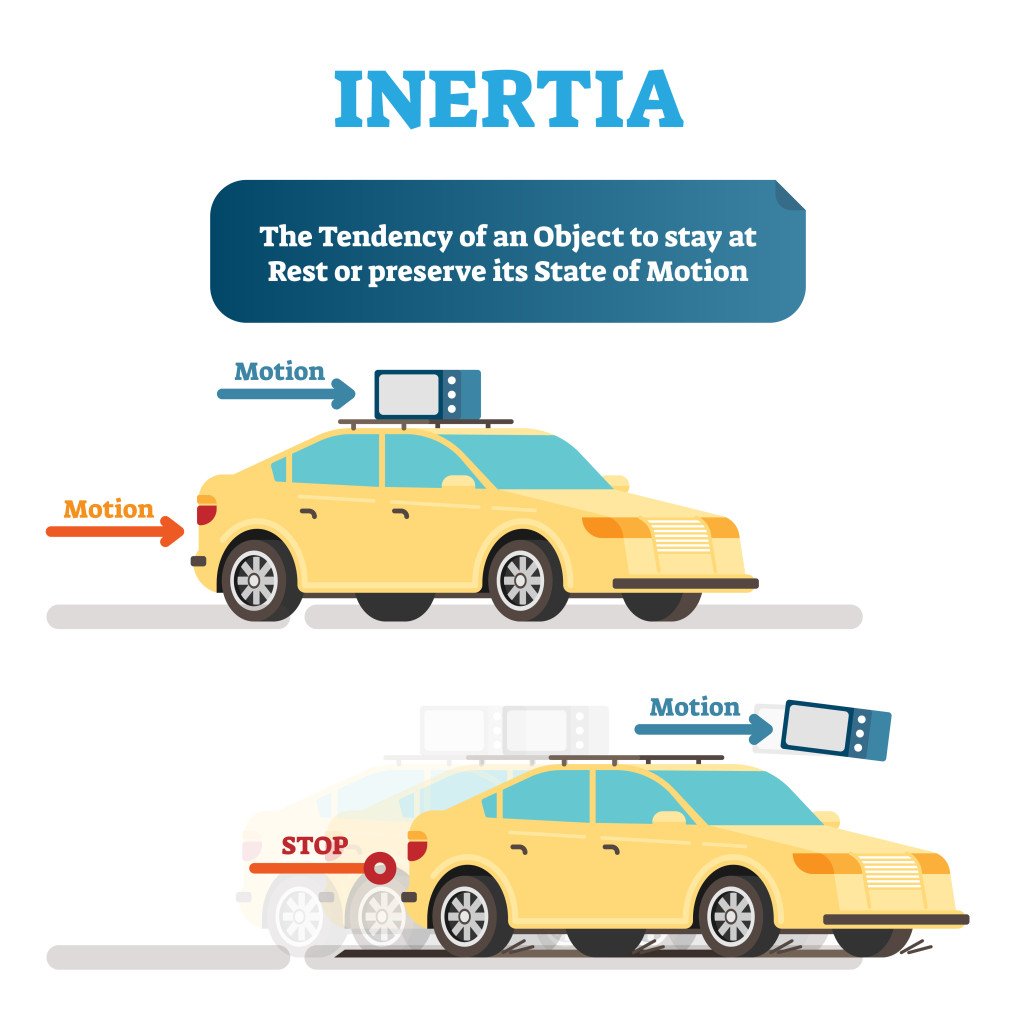

Ships aren’t exactly compact vehicles, so ensuring that the cargo doesn’t tumble around and break a bone or handle every time a wave passes beneath the ship is a top priority for the manufacturer. Now, this is where the laws of physics come into play. More specifically, the concept of inertia and relative velocity.

Inertia And Relative Velocity

The law of inertia[4] states that if a body is at rest or moving at a constant speed in a straight line, it will remain at rest or keep moving in a straight line at a constant speed unless an external force is applied. This is Newton’s first law of motion. Now, humans cannot feel motion itself. This is because we’re bound to the Earth’s surface by gravity, and any vehicle we travel in is also bound to the Earth by the same gravity. We cannot inherently feel the motion of any vehicle while it is traveling at a constant speed.

We can, however, feel its motion if the speed changes, i.e., when it accelerates or decelerates. When we’re inside the vehicle, our relative velocity with the vehicle is 0, i.e., there is no relative motion between us and the vehicle. We are moving with the vehicle inside it.

However, when the vehicle accelerates or decelerates, its speed changes. According to the law of inertia, since we are inside the car, our speed will also change, right along with the car.

The thing is, this process is not instantaneous. The force applied when you press the brakes or the accelerator, or pass over a bumpy road, may take some time to bring you to the same speed as the vehicle, so you are able to feel the speed of the vehicle changing, subsequently “feeling” its motion.

Physics In Real-world Motion

To help you understand the concept of inertia better, let’s take the example of a moving car. When you sit in a car, no matter how fast it’s moving, the only reason you’d be able to tell whether it’s actually moving is looking out at the world moving past the window.

If blinds were placed on the windows, all you’d feel would be the vibrations of the engine while in use. There’d be no way to tell with absolute certainty whether the car was moving or if the engine was simply being revved up as the car stayed in one place.

Now, if the car runs over a speed breaker or a bumpy road, you’d start feeling the movement of the car. Additionally, if the car came to a stop or suddenly started moving, you’d be able to feel some change in the state of rest or motion of the car. This is due to inertia. The same principle would apply to a ship.

Since water bodies are constantly marred by waves that affect the velocity of any ship traveling on them, and vehicles traveling by sea are far more susceptible to turbulent weather conditions, due to the lack of an anchor holding them to the sea bed, you would definitely be able to feel the motion of the ship on such waters.

Can You Feel The Movement Of A Ship Onboard?

So, the answer to the question of whether you’d feel the motion of a ship while onboard is not black and white. You won’t inherently feel the motion of the ship you’re traveling aboard. However, due to the turbulent and unpredictable nature of water bodies, in general, the ship won’t be able to travel with a constant velocity.

Most modern ships are built to withstand changes in velocity, in terms of preventing their passengers from feeling most or any of those changes. However, in the case of any particularly turbulent traveling conditions, you will certainly feel the motion of the ship, so be careful loading up at the buffet line if you’re headed for rough waters!

References (click to expand)

- Drake, S. (1964, August). Galileo and the Law of Inertia. American Journal of Physics. American Association of Physics Teachers (AAPT).

- Sciama, D. W. (1953, February 1). On the Origin of Inertia. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Oxford University Press (OUP).

- LAWTHER, A., & GRIFFIN, M. J. (1986, April). The motion of a ship at sea and the consequent motion sickness amongst passengers. Ergonomics. Informa UK Limited.

- Golding, J. F. (2016). Motion sickness. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Elsevier.