Table of Contents (click to expand)

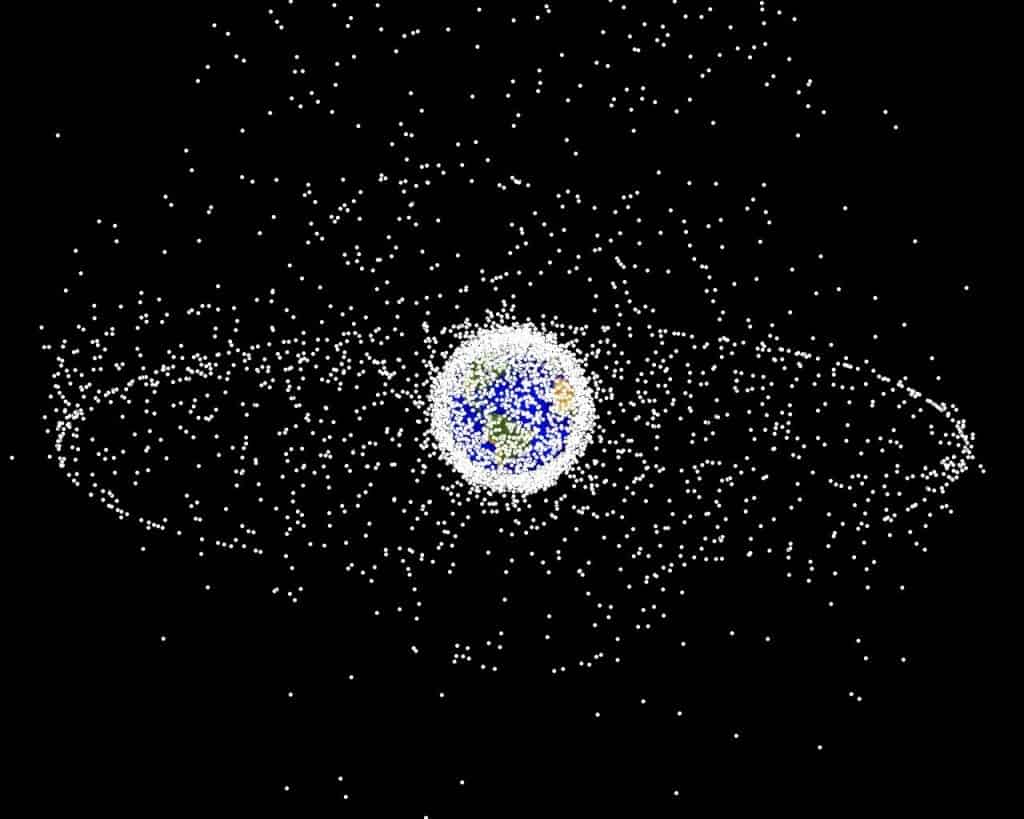

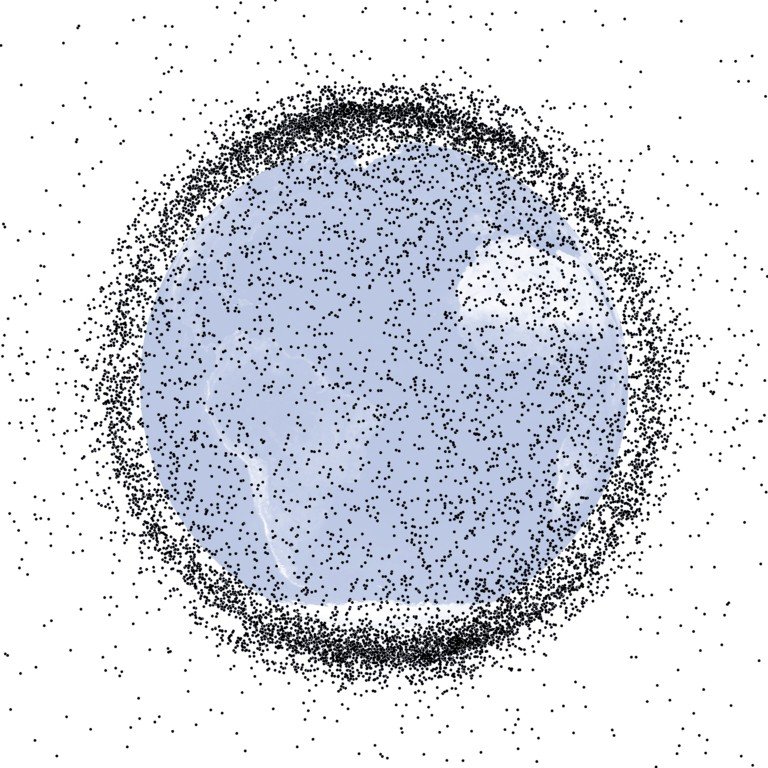

Kessler syndrome is a situation wherein the density of objects in the Low Earth Orbit grows so high that collisions between two objects could cause a massive cascade, wherein those collisions generate more space debris, which, in turn, increases the likelihood of further collisions.

Back in 2017, there was a lot of talk about how the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) set a world record by launching no fewer than 104 satellites from a single rocket! With this bold move, the ISRO smashed the previous record held by Russia, which launched 37 satellites in a single mission back in 2014.

We often see news of satellites being launched by various space agencies all over the world. Everyone is launching satellites these days, or at least it seems that way!

However, have you ever thought about what happens when a satellite ‘dies’? In other words, when a satellite becomes inoperative, what happens to it? Where does it go?

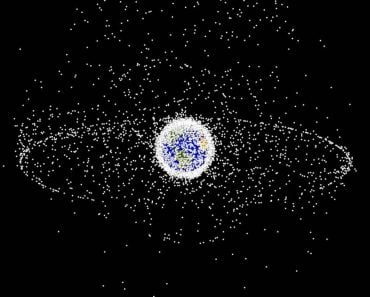

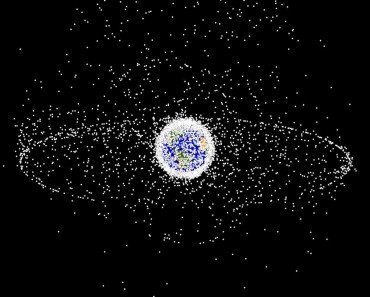

As you can imagine, a dead satellite doesn’t have anywhere to go, so it remains in its orbit (unless the ground staff has other plans for it). With so many satellites in the Low Earth Orbit (LEO), you can imagine how crowded it must be by now. And given the ever-increasing number of dead satellites, it only makes this orbital region more cluttered.

The logical question is, of course, what happens when there are just too many satellites in the orbit?

Impacts and collisions!

Recommended Video for you:

What Is The Kessler Syndrome?

Kessler syndrome is a situation wherein the density of objects in the Low Earth Orbit grows so high that collisions between two objects could cause a massive cascade, wherein those collisions generate more space debris, which, in turn, increases the likelihood of further collisions.

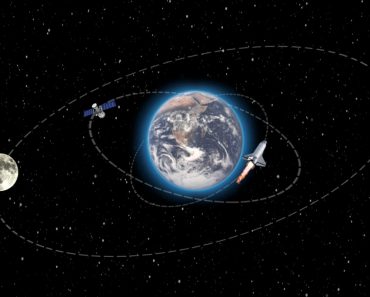

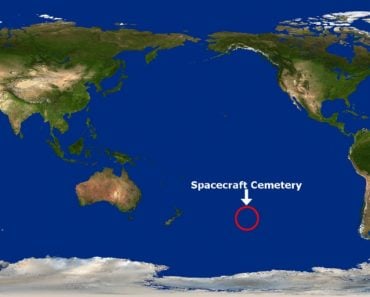

You see, the Low Earth orbit is home to thousands of artificial satellites, along with the International Space Station, the manned artificial satellite that houses 6-8 astronauts at all times. When some of these satellites become inoperable, they are either pushed into the graveyard orbit or they keep circling the planet until they gradually lose altitude and fall towards the Earth, burning up as they re-enter the atmosphere.

The Problem Of Space Debris

While these ‘junk’ satellites or parts of them still circle in the orbit, they pose a great threat to other satellites, spacecraft and even astronauts operating in the same orbit. Do you remember the 2013 blockbuster hit Gravity? The protagonist of the movie was flung out into space because the spacecraft she was on was hit by the flying debris of a decommissioned Russian satellite.

A NASA scientist Donald J Kessler first discussed the problems caused by ‘space junk’ in a paper titled Collision Frequency of Artificial Satellites: The Creation of a Debris Belt, which was published back in 1978. He described a self-sustaining cascading collision of space debris in the Low Earth orbit. This phenomenon came to be known as the Kessler Syndrome, or the Kessler Effect. It’s also known as collisional cascading or an ablation cascade.

According to NASA, the number of debris particles smaller than 1 cm (0.4 inch) is in the tens of millions. The population of particles in the size range of 1-10 cm (0.4-4 inches) is estimated to be around 50,000. The really big ones, i.e., objects larger than 10 cm (4 inches), are more than 22,000 in number. These are the pieces of debris currently being tracked by the US Space Surveillance Network.

Effects Of The Kessler Syndrome

The Kessler Syndrome is bad news because impacts between objects of sizable mass can cause significant damage to ‘useful’ objects that are present in LEO. Not only that, but the resulting debris cascade could also make it extremely difficult to launch satellites in the LEO in a way that they wouldn’t be hit by flying debris. Finally, the long-term viability of new satellites in the LEO would become decidedly low.

Kessler Syndrome (Space Debris) Solution

The most important thing we can do right now is be prudent about what we send into the LEO. Preventing the unnecessary creation of additional orbital debris is the most practical and effective thing we can do to keep Kessler Syndrome at bay. This can be done by designing space vehicles that can somehow be completely removed from the LEO at the end of their operational life.

Cleaning up the existing clutter in the LEO remains a technical and economic challenge that has yet to be overcome by some of the leading space agencies and thinkers of the world.

So, until a more reliable solution is found, prudence is the name of the game!