Table of Contents (click to expand)

There is no clear answer to this question as the mechanism for determining a creature’s lifespan is hotly contested. Some of the strongest contenders for an explanation include total energy expenditure and an upper limit to the number of cell division cycles.

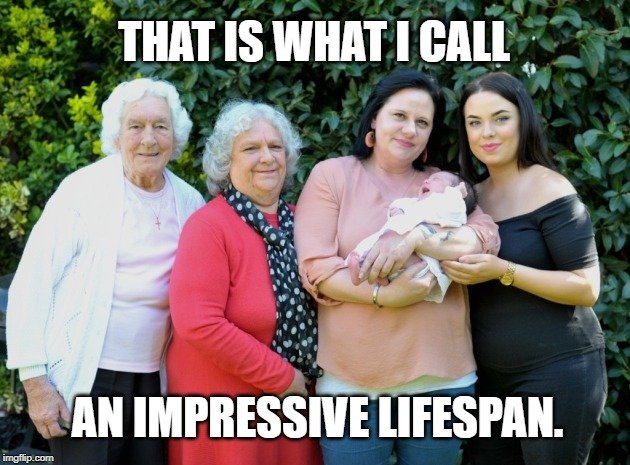

Family reunions are incredibly unique experiences for humans, as it is remarkable to see the breadth and difference in relatedness between people who share the same genes. From the freshest infant to the most wrinkled matriarch—topping out at over a century in age—a family portrait can include three, four or even five generations! There are no other species on the planet who regularly gather family members for portraits, and there are extremely few species on the planet with the longevity where so many generations will simultaneously be alive at the same time!

Yes, as many scholars and laypeople have noted throughout history, human beings seem to have an unusually long lifespan, in comparison to the majority of life on Earth, particularly similarly sized mammals. While there have been many theories proposed as to why this is the case, there is still some ongoing debate as to what determines the lifespan of different species.

Before we get into the unique situation of modern humans, looking back into our own past may give us a bit more perspective.

Recommended Video for you:

Human Lifespan In The Past

Believe it or not, the oldest human being in history—so far as we know—was a 122-year-old French woman named Jeanne, who died in 1997. However, people living to a century or longer is no longer an unusual occurrence; in fact, you may know someone who has aged into the triple digits! We take this as commonplace now, but it is important to remember that a mere two centuries ago, the human life expectancy was much shorter. It is widely believed that the global life expectancy in the year 1900 was only 31 years of age. Our rapid advancement of medical knowledge and expertise in the 20th century, and the globalization of such knowledge to far-flung parts of the world, elevated that life expectancy across the globe to roughly 72 years of age in 2014.

What this means is that for hundreds of thousands of years, as Homo sapiens was developing into a species and coming into their own, they likely had a lifespan of no greater than 30 years. You can compare this to the lifespan of chimpanzees, which average 40-50 years in the wild, and 50-60 years in captivity, or gorillas, who live for roughly 40 years. Considering how closely related we are to the great apes—sharing roughly 99% of the same DNA as chimpanzees and bonobos—our rather impressive modern lifespan can be understood. After all, humans today also have the advantages of agricultural and medical technology, shelter, weather predictions… the list goes on and on. In other words, humans do a good job of keeping themselves healthy, protected and alive well into their old age.

Although the average life expectancy around the globe has been consistently rising for the past century, there is the question of whether there is a cap on human life, or whether ongoing medical advancements will make it so that 100 is the new 72. While this gives us some perspective on our present longevity, it doesn’t necessarily answer the basic question….

Why Do Humans Live For So Long Compared To Most Other Species?

As mentioned above, the exact mechanism for determining a creature’s lifespan is hotly contested, but some of the strongest contenders for an explanation include total energy expenditure and an upper limit to the number of cell division cycles.

Energy Expenditure

In comparison to most other species, humans and great apes take a long time to reach maturity. For example, newborn horses are able to walk with 90 minutes of birth, whereas humans often don’t walk for 1-2 years. Some species of shrew, which are mammals like humans, live for less than a year, and often die within a few weeks of their one and only brood of offspring. Humans, on the other hand, don’t sexually mature for at least a decade, and the average age for women giving birth to their first child in countries around the world range from 18-31 years of age.

All of this is to say that other species develop, mature and reproduce much quicker, and thus require much higher intakes of energy, because their energy expenditure is so much higher. The shrews mentioned above eat close to their weight in insects every day, because their metabolism is incredibly fast, with a heart that beats more than 600 times per minute!

Generally speaking, other species develop and reproduce more rapidly, reaching adulthood within 1-2 years, and reproducing as often as possible during their viable period for reproduction. Humans and other primates are exactly the opposite of that, and their metabolic rate is correlatively lower—about half the rate of other mammals. Cellular respiration and energy expenditure wear an organism and its systems down more rapidly, whereas having a more relaxed metabolic rate can help to extend life by decades.

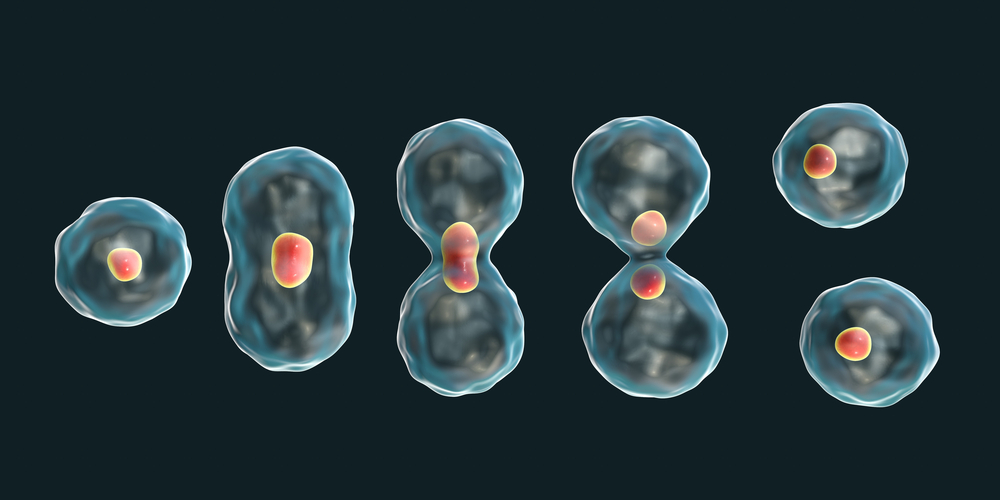

Cell Divisions (Hayflick Limit)

Another potential explanation is an in-built limit to the number of times that a cell population can divide before becoming senescent, i.e., unable to divide further. This limit is called the Hayflick Limit, and for humans cells, it is found to be approximately 50 division cycles. This expiry date on cell’s dividing ability seems to hint at a natural cut-off point for human life, and it seems to hold up across other animals. Species with notoriously short lifespans, such as mice (2-3 years) have a Hayflick Limit of 15 divisions, while animals with even longer lifespans than humans have a higher Hayflick Limit (e.g., sea turtles, with a life expectancy of over two centuries, have a Hayflick Limit of approximately 110).

As cells age, their telomeres decrease in length, eventually making further, accurate cellular division impossible. The direct connection between telomere length, the Hayflick Limit and lifespan is not clear, if it exists at all.

A Genetic Connection?

In a number of other simplistic species, a gene has been found that effectively limits lifespan by activating other genes that control everything from transcription and protein production to reproductive triggers. It was found that when this single gene was mutated in certain earthworms, their lifespan could as much as double. This gene appears to be an early precursor to a gene that controls insulin production in humans, which may also work as a control mechanism for the inhibition and activation of other genes. These discoveries are exciting, as they may hint at an underlying genetic blueprint for an organism’s lifespan. For researchers seeking the “fountain of youth” or “immortality”, these research frontiers are particularly exciting.

Exceptions To The Rule

Now, while humans do have the potential to live for a century or more, we are by no means the longest-living organism on the planet. The giant tortoises found on the Galapagos Islands have been known to live for over 150 years, while the Greenland Shark’s oldest specimen is more than 400 years old! In terms of invertebrates, there are some clam species that can also live for more than 5 centuries!

Yes, it is rather remarkable that human life expectancy has more than doubled in the span of only a century, but from what we know thus far, or can practically apply, there is an average cap to how long we can live. As cells and tissues become older and have more errors in their genetic coding, the body begins to break down, disease is more likely, and the ability to heal is hampered. As we all know, life is unpredictable, so it’s best to existence while you can!

References (click to expand)

- Genetic Control of Aging and Life Span - Nature. Nature

- Bonobos Join Chimps as Closest Human Relatives - Science. sciencemag.org

- Mather, K. A., Jorm, A. F., Parslow, R. A., & Christensen, H. (2010, October 28). Is Telomere Length a Biomarker of Aging? A Review. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. Oxford University Press (OUP).

- Limits on Cell Life Span Have Little To Do With ... - Fight Aging!. fightaging.org

- Finch, C. E. (2009, December 4). Evolution of the human lifespan and diseases of aging: Roles of infection, inflammation, and nutrition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Shay, J. W., & Wright, W. E. (2000, October). Hayflick, his limit, and cellular ageing. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.