Table of Contents (click to expand)

Shrew, a tiny mole-like animal, has been found pooping in carnivorous pitcher plants in the tropical forests of Borneo. Oddly enough, the plant seems to be luring the shrew to poop inside it!

Plants grow in deserts, the arctic, and even under the sea. So why on Earth would a pitcher plant need a tree shrew’s poop in the middle of a tropical rainforest?

While sugars and carbohydrates come easy to plants, proteins and pigments made of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium are much more difficult to acquire. Humans use fertilizers to ensure that crop plants have what they need to grow, but where does one find fertilizer in the middle of a rainforest?

Poop, of course!

Recommended Video for you:

How Do Plants Meet Their Nitrogen Requirements?

Plants have met their nitrogen requirements for millions of years, long before humans came along and invented fertilizers. So how did they do this? Cooperation!

Nitrogen is the most abundant gas in the atmosphere, so it’s puzzling why plants should find it scarce. This is because nitrogen is already there in the air, but not in the soil, where plants could absorb it. Rhizobium bacteria can take nitrogen from the air and churn it into the soil. Plants rely on this, and in return, Rhizobium are provided sugars and shelter by the plant.

Another method by which plants get nitrogen is far less cooperative – carnivory. We’ve all heard of the Venus Flytrap, which snaps its jaws shut around unfortunate flies and other insects. The incredible bladderwort uses suction force to draw insects into its door-like traps. Even the juvenile pitcher plant Nepenthes lowii uses nectar on its lid to draw unsuspecting insects inside.

Adult Nepenthes plants get their nitrogen from a slightly more discomfiting source. Like their youthful forms, they use nectar to lure organisms in. Rather than insects, they bait shrews, a small rodent-like mammal. As the shrew enjoys its meal of nectar, it takes care of its morning business.

At that point, plop goes the poop into the pitcher, and whoosh goes the nitrogen into the plant.

In the lush, verdant rainforests of Borneo, it is difficult to imagine plants facing a scarcity of anything at all. However, it is precisely after millions of years in these nitrogen-poor soils that such a fascinating interaction arose.

How Did Researchers Figure Out The Shrew-pitcher Plant Relationship?

It is difficult to imagine how exactly scientists were able to decipher the nature of this relationship.

Imagine you see a Nepenthes plant, with flowers of two types. One floats above the ground, known as the aerial plant, while another lies along the ground like a creeper. At first, all Nepenthes plants have exclusively ground flowers, but as they age, all the flowers become aerial.

The first thing you might wonder is why there are two different flowers. Upon looking closer, the terrestrial flowers are covered with a thin, waxy layer. This layer makes it hard for ants and other arthropods to find purchase, so they slip down the lid into the pitchers. Aerial flowers do not seem to have this waxy layer, indicating that they might serve a different purpose.

When observing these flowers for a while, you would see insects regularly visiting, and dying, in the ground-dwelling plants. In the aerial plants, you would observe something quite unusual. Shrews make regular rounds to the same plants over and over, developing something of a circuit. They visit the plants on their route between noon and sunset.

But why would the shrews visit? Producing nectar costs the plant energy, so unless the shrews are thieves, plants should be getting something from the shrew. You know that aerial and terrestrial flowers look different, and that insects caught by terrestrial flowers provide nitrogen.

As we know, correlation (the shrew visiting) does not mean causation (the shrew somehow provides the pitcher plant with nitrogen).

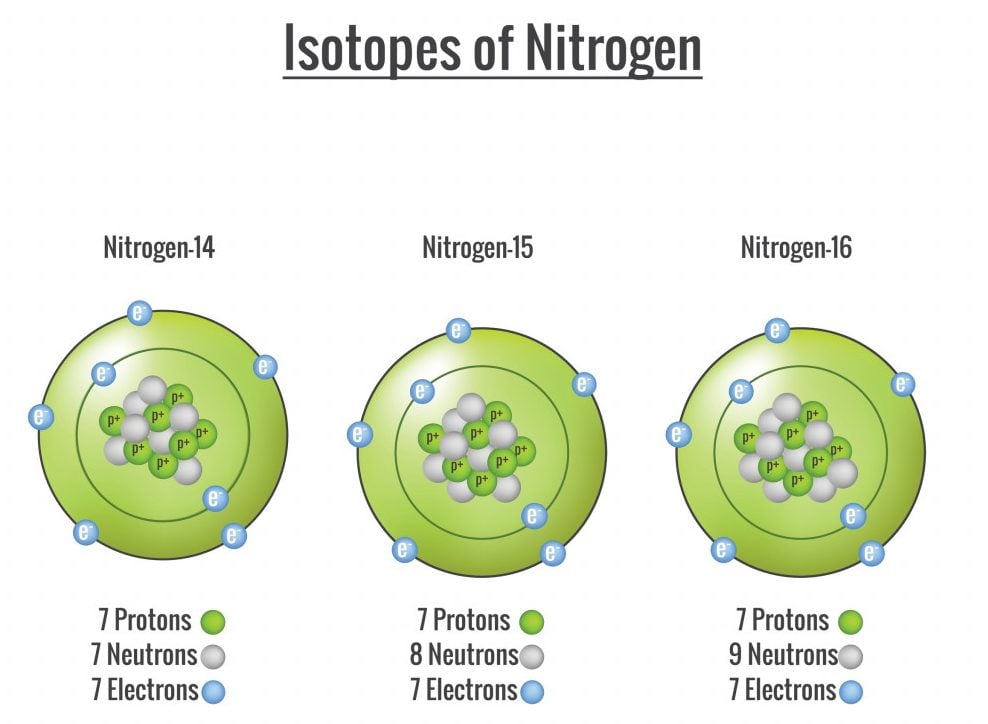

To investigate whether the pitcher plant indeed gets its nitrogen from the shrew, researchers turned to Nitrogen-15.

Nitrogen-15 is a stable isotope of nitrogen. It contains the same number of protons and electrons as the most common isotope, nitrogen-14, but a different number of neutrons. Nitrogen-15 and nitrogen-14 are the only stable forms of nitrogen that exist. Approximately 99.6% of all nitrogen is nitrogen-14, but a rare 0.4% of it is nitrogen-15. Everything that contains nitrogen contains it in roughly these same proportions.

In order to find out just how much nitrogen the pitcher plant was getting from shrew poop, they compared the difference between the amount of nitrogen in the leaves between the aerial and terrestrial pitchers of similar species. They also needed to find out how much Nitrogen-15 was in shrew poop, as compared to the terrestrial pitcher of the similar species.

In short, they traced how much Nitrogen-15 was in shrew poop to see how much ended up in the aerial pitchers.

They found out that an astounding 57% of nitrogen in aerial lowii pitchers comes from shrew poop. The symbiosis between the shrew and the pitcher plant is not insignificant—without this relationship with shrews, aerial pitcher plants would not survive at all!

Conclusion

Plants have evolved to overcome scarcity in truly astounding ways. Who would have guessed that pitcher plants would use nectar to bait a specific species of shrew, and then use its poop as a nitrogen source? While poop might not be worth its weight in gold to you, it is certainly a matter of life and death for the pitcher plants of Borneo.

Just as plants got creative, researchers got creative too. While it might be easy to observe a correlative relationship in nature, it often requires a leap of faith or a clever use of technology to investigate how exactly a phenomenon takes place!

References (click to expand)

- Clarke, C. M., Bauer, U., Lee, C. C., Tuen, A. A., Rembold, K., & Moran, J. A. (2009, June 10). Tree shrew lavatories: a novel nitrogen sequestration strategy in a tropical pitcher plant. Biology Letters. The Royal Society.

- He, X., Xu, M., Qiu, G. Y., & Zhou, J. (2009, August 18). Use of 15N stable isotope to quantify nitrogen transfer between mycorrhizal plants. Journal of Plant Ecology. Oxford University Press (OUP).