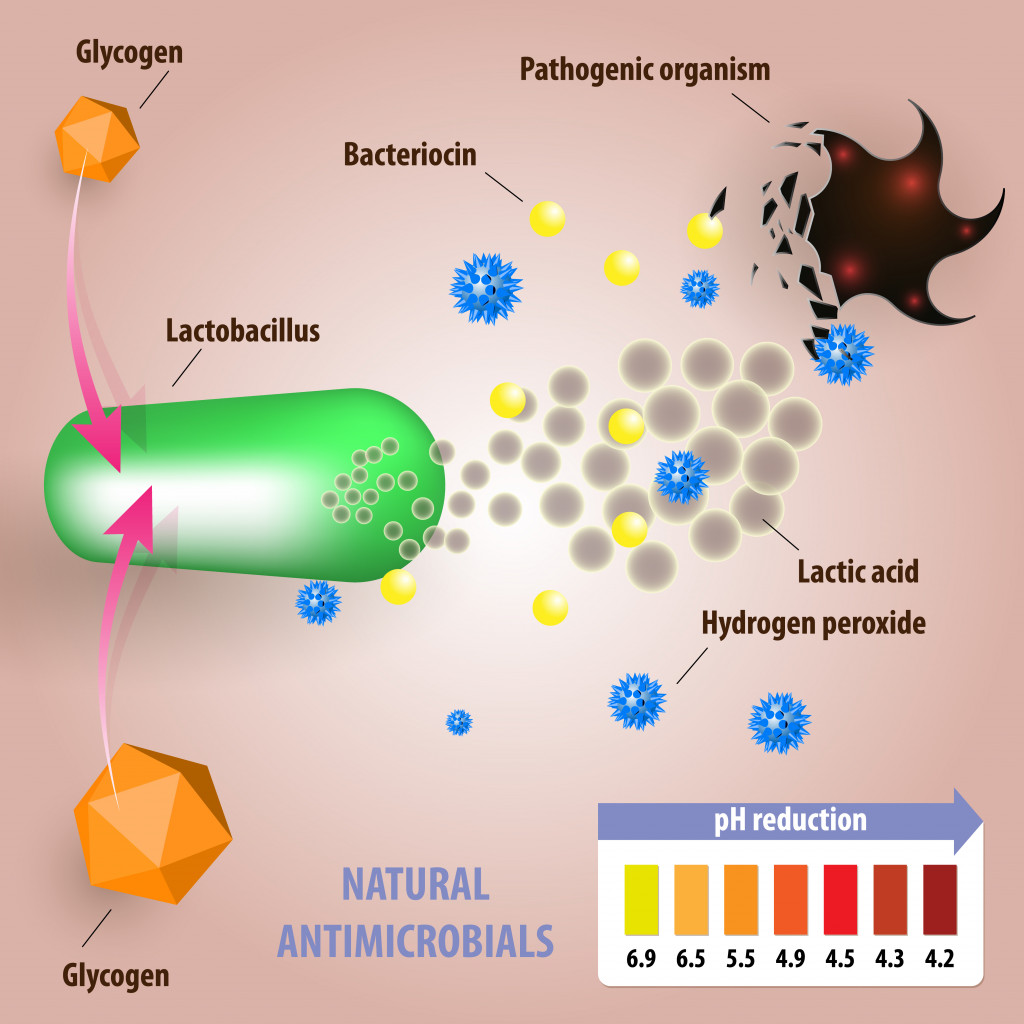

Helpful bacteria keep pathogenic bacteria at bay by secreting toxic molecules that can kill potential pathogenic bacteria, thickening our protective mucus lining and keeping the gut acidic.

The human microbiota—the intestinal microscopic multi-trillion tenants living inside us. Amongst these trillions lies both helpful and not-so-helpful gut bacteria. The helpful ones are what we commonly refer to as good gut bacteria, and they help us digest our food, make essential nutrients, get a good night’s sleep and affect our hormones and moods.

Humans and their gut bacteria have a give-and-take relationship. They help us with biological functions, and in return, they want food and a place to stay. The thing is, the good and bad bacteria must fight each other to stay in the limited real estate of our gut. Thankfully, the good ones help keep those that make us a mess of puke and diarrhea at bay.

Recommended Video for you:

Gut Bacteria Release Pathogen-killing Chemicals

Good gut bacteria fight pathogenic bacteria with their own molecular ammunition.

Bacteriocins are a diverse group of anti-bacteria protein molecules that either break down important cellular components of bacteria or inhibit essential enzymes that are needed to make their cell wall or DNA.

Good gut bacteria like E.coli make plenty of bacteriocins and flood our gut with it. If any invading bad bacteria try to enter the gut through bad food or water, they are immediately met with a bombardment of bacteriocin molecules that try to kill them.

Lactic acid bacteria species present in the gut produce bacteriocins that kill other dangerous disease-causing bacteria, like Listeria monocytogenes. Listeria comes from eating spoilt meat or raw unwashed vegetables and can cause severe food poisoning.

Some bacteriocins like lugdunin, made by Staphylococcus lugdunensis, can activate immune cells in the skin and stimulate them to make antimicrobial molecules that target bad bacteria.

This is a more offensive method. Gut bacteria also have a defensive approach, wherein they attempt to make the gut inhospitable to other bacterial species.

Gut Bacteria Make The Gut Inhospitable To Bad Bacteria

What’s the best way to keep unwanted people out of your home? Make the home uncomfortable to stay in, of course!

Let’s say two siblings—Aye and Bee—are sharing a room, and Bee wants the room to themselves. Bee lets out a smelly fart, forcing Aye to leave the room, and then keeps it stinky enough so that Aye doesn’t come back.

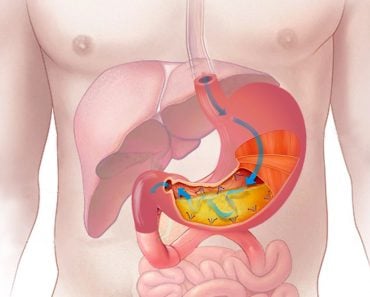

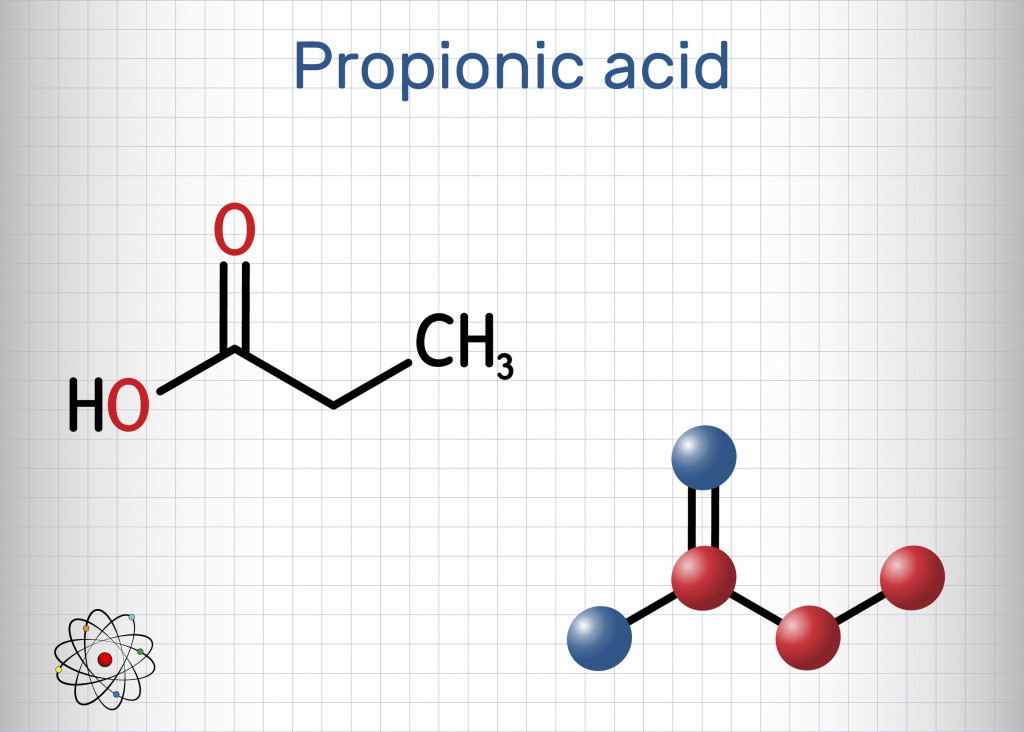

Similarly, good gut bacteria help keep the gut pH acidic by producing short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as propionic and butyric acid, when they break down the food you eat. The pathogenic bacteria that we don’t want crowding our gut don’t like acidic environments, so this stops them from growing freely and settling in the gut.

Bifidobacterium, a prominent but normal gut bacteria that is also commonly consumed as a probiotic, helps keep the gut environment acidic. This stops pathogenic E.coli strains from settling in the gut.

The short-chain fatty acids also suppress undesired bacterial growth by preventing their disease-causing genes from being expressed. For example, one study conducted on mice found that butyrate suppresses S. Typhimurium growth, the bacteria that causes typhoid in mice. It stops S. Typhimurium from expressing its disease-causing genes, so it’s not able to cause gut infections.

Short-chain fatty acids also stimulate the immune cells present in the gut to secrete defensive antimicrobial protein molecules like LL-37 that kill certain bacterial species, such as Pseudomonas.

Gut Bacteria Compete With Each Other For Nutrients

What’s the main problem associated with Earth’s growing population? We’re running out of resources for everyone. The same holds true for nutrients present in the gut. The food we swallow makes its way to the lower gut for further digestion. Here, the gut bacteria treat it like a buffet. They lie steady, waiting, ready to snatch up the food that comes their way.

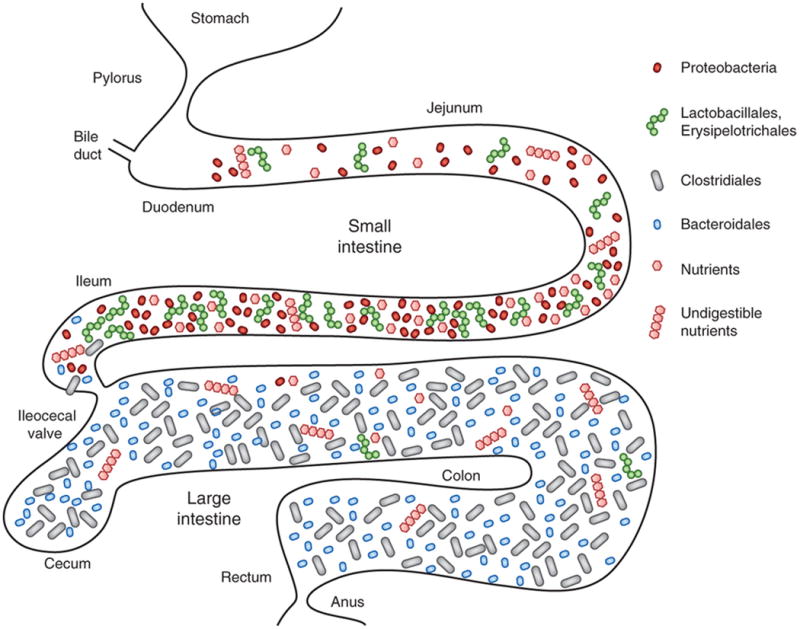

Different gut bacterial species are present in their own little regions in the intestine. They thrive in particular spots according to the nutrients they need, depending on the digestion stage. Different bacteria produce different metabolites and short-chain fatty acids, which results in different pH values throughout the gut.

Even though it’s the same gastrointestinal tract, there are different microenvironments within it that are home to different gut bacteria species. This creates a delicate system balance between bacterial species where they tend to stay in their own territory.

This system doesn’t allow for extra hands grabbing for nutrients, especially from pathogenic bacteria that ideally should not be growing in the gut at all. By snatching all the nutrients, like carbohydrates, iron, sulphur, etc., the good gut bacteria keep the bad ones from accessing the nutrition they need to grow.

Additionally, good gut bacteria can use those nutrients to make more antimicrobial molecules that kill bad gut bacteria.

Gut Bacteria Strengthen The Physical Barriers In The Gut

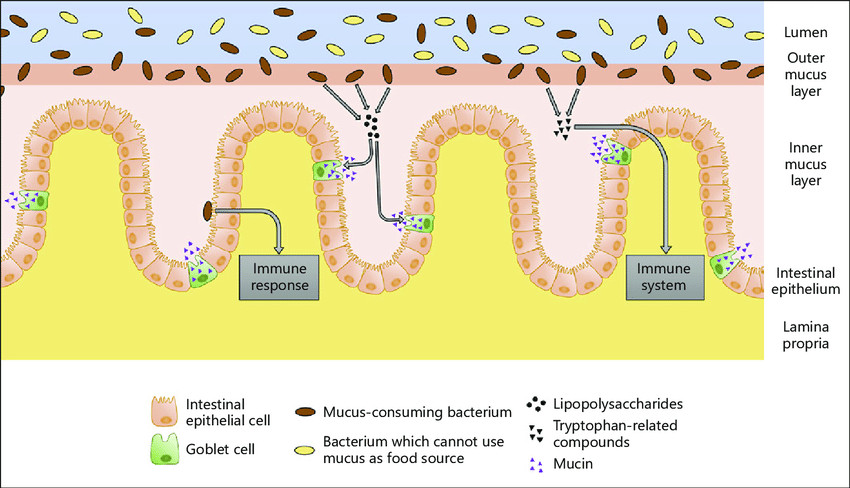

The inner walls of the gut are lined with slimy mucus secreted by cells in the intestinal epithelium. This stops the microbes from attaching to the inner surface of the gut and breaching our body. This mucus also contains proteins capable of harming bacteria, such as Muc2.

However, mucus can’t always stop bacteria from attaching to the gut, as bacteria have certain adherence factors that help them stick to the inner gut’s surface.

They can use pili, which are tiny hair-like extensions that help them stick to surfaces. Many species also produce exopolysaccharides, which are sticky sugar molecules, or bacterial jellies, that help them stick to the inner gut surfaces. These sugar molecules play a role in biofilm formation, which helps bacteria protect themselves from antimicrobial molecules like Muc2.

Once attached to the gut lining, the bacteria’s presence stimulates the intestinal epithelial cells to produce more mucus. As the mucus thickness and quantity increases, it makes it increasingly difficult for pathogenic bacteria to attach themselves to the inner gut surface.

In many ways, this is a first-come, first-serve situation; good gut bacteria attach themselves to the gut and then make life difficult for any other bacterial species that is trying to gain a foothold and survive.

A Final Word

Unfortunately, pathogenic bacteria have strategies of their own to fight back. They can similarly stop good gut bacteria from getting essential nutrients. If we eat sugar-rich junk food that is preferred by the bad gut bacteria, they can begin to outnumber the good ones and turn the tide in our microbiota!

Bad gut bacteria can also produce their own bacteriocins and proteins that help them evade our immune cells.

In such unhealthy conditions, when the gut environment isn’t favorable, our helpful bacteria can even turn into disease-causing ones. This is when the gut becomes imbalanced, along with the gut microbiota, leading to a condition called dysbiosis.

Just remember, the buck stops with us. A good diet and lifestyle, along with additional reinforcements like probiotics and prebiotics, can boost good gut bacteria growth and keep our bodies operating at their best!

References (click to expand)

- Pickard, J. M., Zeng, M. Y., Caruso, R., & Núñez, G. (2017, August 30). Gut microbiota: Role in pathogen colonization, immune responses, and inflammatory disease. Immunological Reviews. Wiley.

- Kamada, N., Chen, G. Y., Inohara, N., & Núñez, G. (2013, June 18). Control of pathogens and pathobionts by the gut microbiota. Nature Immunology. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Okumura, R., & Takeda, K. (2017, May). Roles of intestinal epithelial cells in the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Heilbronner, S., Krismer, B., Brötz-Oesterhelt, H., & Peschel, A. (2021, June 1). The microbiome-shaping roles of bacteriocins. Nature Reviews Microbiology. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Martín, R., Miquel, S., Ulmer, J., Kechaou, N., Langella, P., & Bermúdez-Humarán, L. G. (2013, July 23). Role of commensal and probiotic bacteria in human health: a focus on inflammatory bowel disease. Microbial Cell Factories. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Gut bacteria use nutrient to fight off germs. nih.gov

- Sun, Y., & O’Riordan, M. X. D. (2013). Regulation of Bacterial Pathogenesis by Intestinal Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Advances in Applied Microbiology. Elsevier.