“The coloration of titanium results from the interference of light reflected through the oxide layer that forms on it”.

Titanium is the world’s most loved metal, after gold. It is used in a plethora of applications ranging from something as critical as surgery and spacecraft to aesthetic purposes in jewelry and keychains.

This versatile, yet esoteric metal is also one of the most beautifully oxidizing metals, resulting in enrapturing colors and finishes that are second to none. So what gives this otherwise grey and unassuming metal its great looks?

Recommended Video for you:

Titanium – The Metal, The Myth, The Legend?

Titanium is known for its superior mechanical properties, including incredible strength, despite its low density and high corrosion resistance. While it is not considered a precious or rare earth metal, it is quite expensive, as the process of extracting titanium from its ore is very resource-intensive.

Its mechanical properties make it very difficult to work with in terms of processes like fabrication and machining, furthering the costs of the finished product. The process of extracting titanium hasn’t changed much over the years, keeping the entry barrier to the use of this abundant metal very high.

Titanium Oxide – The Cause Of Color

If the precedent of iron is anything to go by, metals aren’t exactly great friends with oxygen. However, this is not true for titanium. Titanium oxidizes through both heat and electric current to form a virtually impenetrable barrier. This barrier exhibits many salient properties, such as mechanical rigidity and visual trickery.

With increase in temperature or voltage, the thickness of the oxide layer increases. Unlike rust, titanium oxide can be stubborn and requires mechanical means to be removed, in order to expose the fresh layer of titanium underneath.

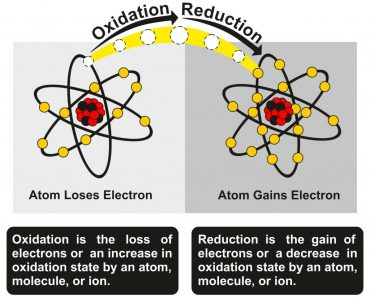

Perception Of Color – Thin Film Interference

None of the coloration seen on titanium due to oxidation can be attributed to changes in chemical composition or the addition of pigment. It is, in fact, a trick played by the oxide layer on the human eye.

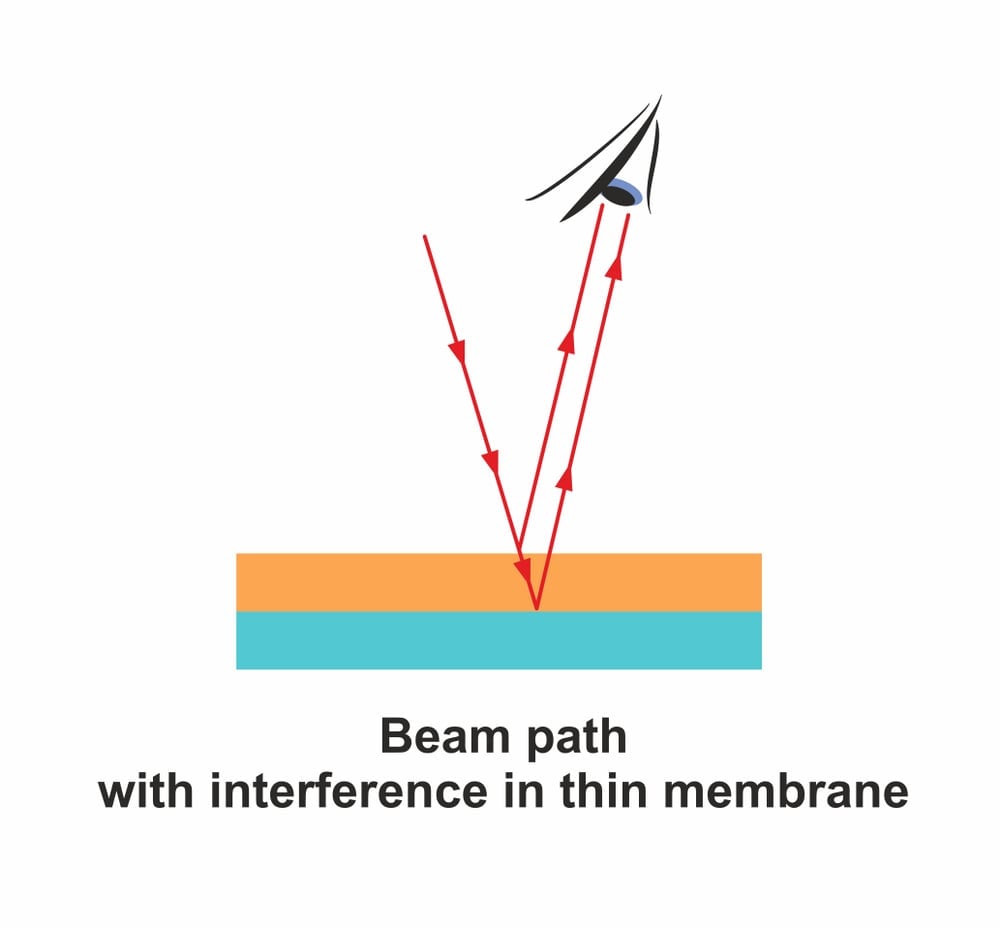

The oxide layer is thin and transparent, causing light to reflect from both over and under it. The reflected light rays interfere, resulting in certain wavelengths of light being cut out, while others are accentuated to produce brilliant colors. This phenomenon is also known as thin film interference.

With an increase in heat or voltage, the oxidation layer gets thicker and more stable. This brings about a change in the refractive index, and results in both discrete and continuous shades. Unless mechanically removed, the coloration on titanium is permanent, even after the removal of heat or voltage.

Oxidizing Titanium – Heat

Traditionally, titanium has been oxidized by heat. Since the flow of heat within the metal cannot be controlled physically, heat oxidizing can be quite a challenging process for achieving a desired, definitive finish. Apart from specialized equipment for even heating, post-processing is required for the removal of oxide layers from undesired areas.

Processes like selective sand blasting and mechanical abrasion, such as sanding, are used for such processing.

The thickness of the oxide layer increases with an increase in temperature. Due to this, various colors of titanium oxides are associated with different temperature ranges.

| Temperature ( °C) | Color of oxide layer |

| 385 | Pale gold straw |

| 412 | Purple |

| 440 | Deep blue |

| 565 | Red purple |

| 648 | Brown gray |

| 925 | Green blue |

Heat treatment of titanium work pieces results in glossy finishes.

Oxidizing Titanium – Voltage

The oxide layer on titanium can also be achieved by subjecting it to electric current when it is dipped in a conducting medium (electrolyte). This is also known as anodizing. The titanium work piece is hooked to the positive terminal of the battery, whereas the negative terminal can be connected to any other metal, such as aluminum, copper or stainless steel.

The thickness of the oxide film remains constant for a given voltage. Thus, various voltages will correspond to different colors. The thickness can, however, be manipulated by changing the nature of the electrolyte.

Acidic and neutral electrolytes are known to produce thinner oxide layers that usually have a range of only a few nanometers. However, strong alkaline media are known to produce coatings that can be several microns thick.

| Applied voltage (V) | Color of oxide layer |

| 6 | Light brown |

| 10 | Golden brown |

| 20 | Dark blue |

| 30 | Pale blue |

| 40 | Olive green |

| 70 | Light purple |

| 100 | Dull green |

Using electricity as a means of preparing colored titanium oxides presents a few advantages over using heat. The flow of electricity can be controlled, while selective dipping and masking allows only the desired areas of the work piece to get colored.

Anodizing titanium is a more feasible solution than heat oxidizing it. This is because the voltage required to produce a certain color is easier to achieve than supplying an equivalent and accurate amount of heat.

Applications

“Colored titanium” finds various aesthetic, medical, industrial and automotive uses. It is used in jewelry, medical tools and implants, sports car exhaust pipes, and heat dissipation modules.

Titanium isn’t the only metal that exhibits coloration. Niobium, tantalum and several steel alloys, such as carbon and stainless steel, also exhibit colouration under distress. However, titanium has unique advantages that make it worthwhile for oxidization. Some of these include biocompatibility, high corrosion resistance, and long-term stability of the oxide layer.

Titanium and its oxides are also light in weight, giving them significant performance advantage over competitive alloys, such as stainless steel. The only downside to using titanium and its oxides is that they are extremely expensive to procure.