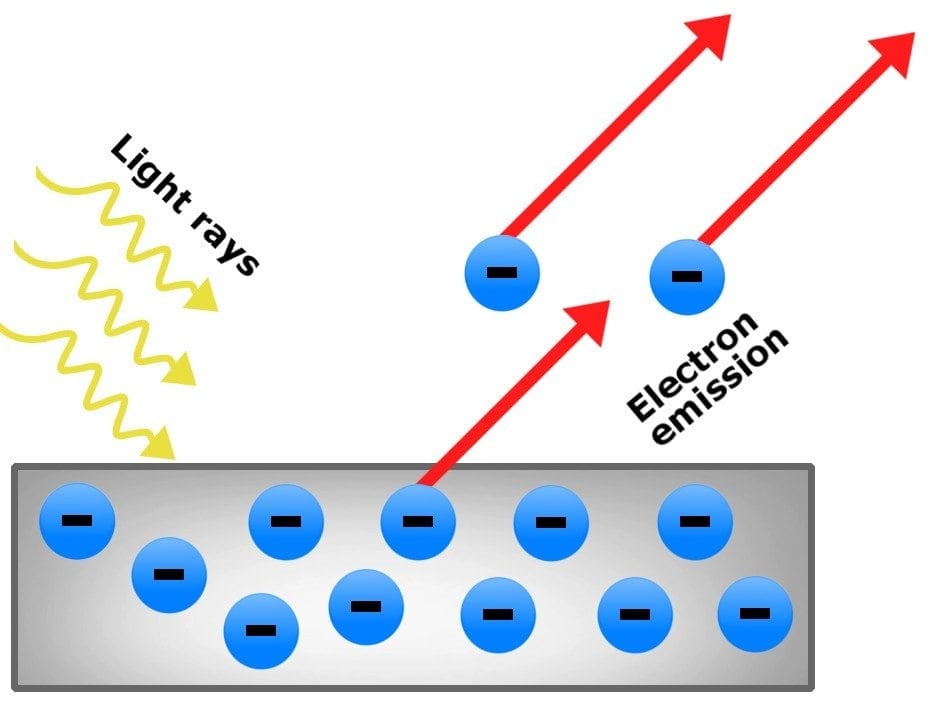

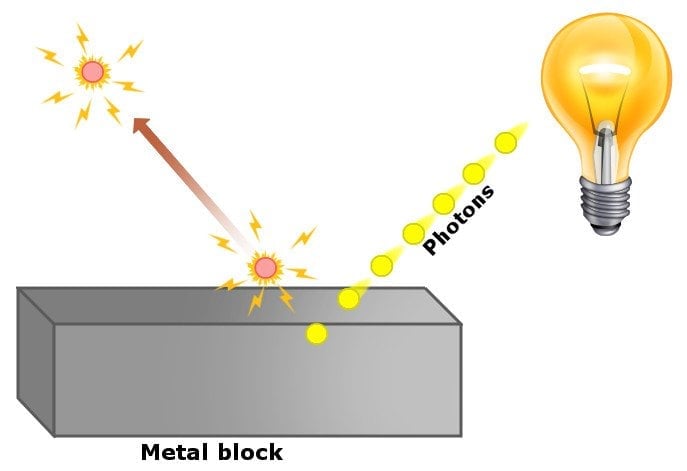

The photoelectric effect is the phenomenon of the ejection of electrons from the surface of a metal when light shines on it. The electrons produced in this way are called photoelectrons.

This phenomenon is attributed to the transfer of energy from photons to electrons. Although such a release of photoelectrons can be observed by shining light rays on any material, it’s most readily observable in metals (and other conductors). The reason behind this is that the incident light ejects electrons from the metallic surface, producing a charge imbalance.

Also referred to as photoemission or photo ionization, it is mostly studied in electronic physics, along with electrochemistry and quantum chemistry.

Recommended Video for you:

How 19th Century Physicists Failed To Explain The Photoelectric Effect Using Classical Physics

Physicists in the 19th century tried explaining the emission of electrons from a metallic surface using principles of classical physics. For starters, classical physics is the branch of physics that does not make use of quantum mechanics or the theory of relativity, which are considered more complete and therefore widely accepted.

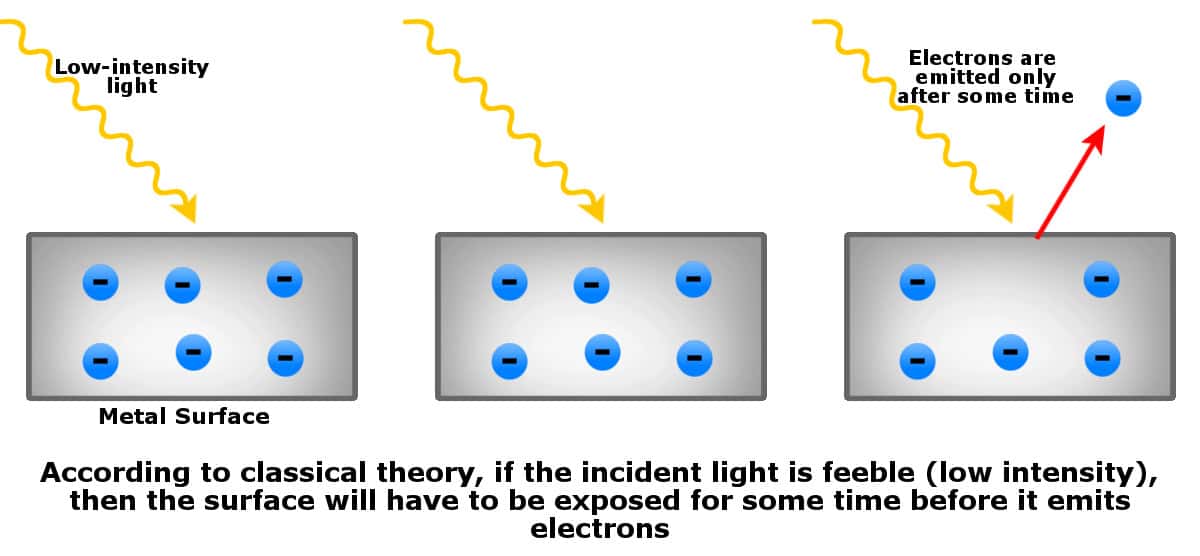

Scientists of classical physics, who considered light a wave, postulated that the oscillating electric field of the light that hits the metal surface heats the electrons present inside them, which, in turn, begin to vibrate. They also believed that the brightness (intensity) of the light wave was proportional to its energy.

Using the wave theory of light, classical physicists made these three predictions:

- The higher the brightness (intensity) of the incident light, the greater the energy of electrons that are emitted from the surface.

- A light wave of any frequency should be able to knock off electrons, provided a reasonable intensity is maintained.

- If the incident light is of low intensity (too feeble), then the metal surface must be continuously exposed for some time until enough waves strike the surface to knock off electrons.

However, when experiments were conducted, the predictions of classical physics turned out to be incorrect…

- The energy of the knocked-off electrons does not depend on the intensity of incident light.

- Electrons are not knocked off the surface unless the frequency of the incident light wave is more than a critical value (threshold frequency).

- Electrons appear as soon as light falls on the metal surface.

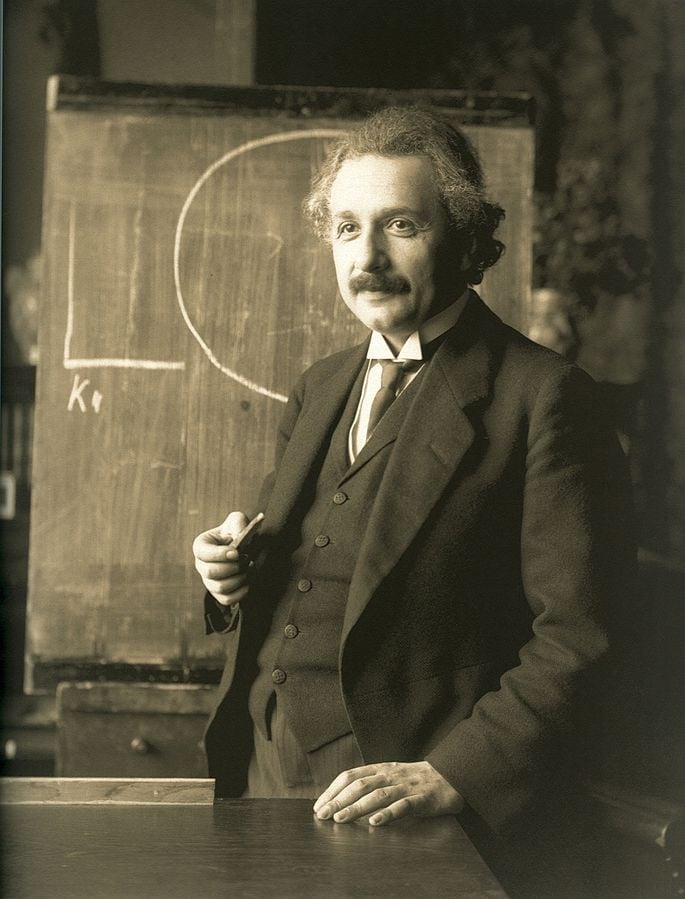

Therefore, scientists of classical physics couldn’t explain the photoelectric effect using the wave theory of light, which is where Mr. Einstein stepped in.

Einstein Explains The Photoelectric Effect

In 1905, eminent physicist Albert Einstein published a paper (in the same issue as his famous paper on relativity) wherein he presented a theory to explain the ‘unexpected’ observations concerning light. To quote him:

In accordance with the assumption to be considered here, the energy of a light ray spreading out from a point source is not continuously distributed over an increasing space, but consists of a finite number of energy quanta which are localized at points in space, which move without dividing, and which can only be produced and absorbed as complete units.

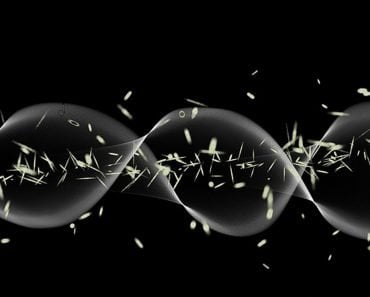

In simple words, he proposed that in experiments concerning the photoelectric effect, light did not behave like a wave, but rather like a particle, which we refer to as a ‘photon’. His theory successfully explained the observations from experiments of the photoelectric effect in this way:

The energy of electrons knocked off the metal surface does not depend on the intensity of light, because an electron absorbs only one photon at a time. If the energy of the photon is large enough, then electrons are knocked off the surface. If not, then the electron dissipates the energy that it got from the photon through collisions with neighboring electrons and atoms.

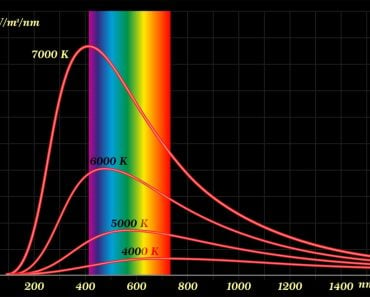

Threshold Frequency

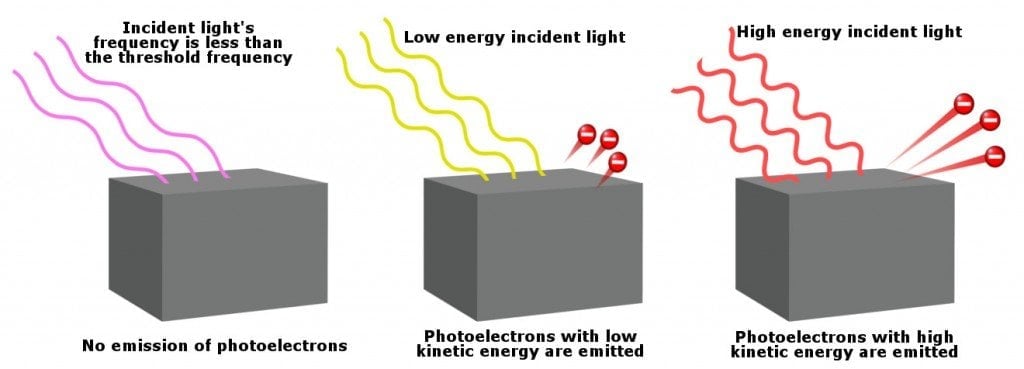

No electrons fly off the surface if the frequency of the incident light is less than a critical value, which is known as the threshold frequency. Given below is a diagram to understand this better:

Note that electrons are not ejected unless the light’s frequency exceeds the threshold frequency. However, for two different light rays with frequencies higher than the threshold frequency, the light rays with higher energy release electrons with higher kinetic energy.

Einstein Won A Nobel Prize For This!

You probably may not know this, but Einstein won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 not for his theory of relativity, but for successfully explaining the photoelectric effect using the particle nature of light.

Applications Of The Photoelectric Effect

The photoelectric effect has a number of applications, but the most obvious, and also the biggest, example would be its use in producing solar energy using photovoltaic cells. These cells are made of semiconducting material that generate electricity when exposed to the sun.

From something as common as a calculator (solar-powered) to large artificial satellites that orbit the planet, there are countless applications of solar energy.

The photoelectric effect was also used in imaging technology (more specifically, in video camera tubes – a type of cathode ray tube used to capture the television image) in the early days of television. Apart from that, it’s used in the chemical analysis of materials based on the electrons they emit, allowing for the study of electronic transitions between energy states and certain nuclear processes.

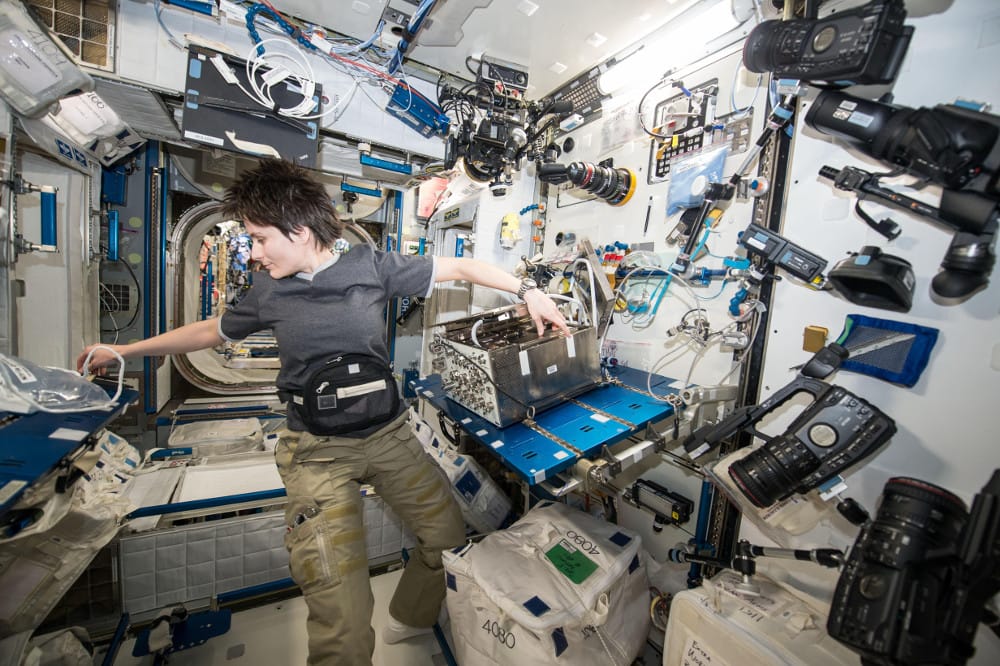

An Undesirable Impact Of The Photoelectric Effect On Spacecraft

The photoelectric effect can lead to the buildup of a net positive charge on the exterior of a spaceship, as its prolonged exposure to sunlight leads to a continuous emission of electrons from its metallic surface. Therefore, the sunlit side of a spacecraft develops a positive charge, while the side in shadow develops a relative negative charge.

This charge buildup across the surface of the spaceship causes electric currents to flow, which is not a good thing, especially when you have delicate circuitry and machinery operating inside the ship.

Therefore, the electrical systems on spacecraft consist of plenty of conductors that prevent such a buildup of net charge on their surface.