Table of Contents (click to expand)

Archaea is the third domain of life—”domain” being the highest categorization level of life on the planet. Archaea microbes have certain characteristics that are more in line with eukaryotes than bacteria, such as more complex enzymes for replication, as well as unique components in their cell membranes.

Humans have spent thousands of years trying to understand life on Earth—our own lives as well as other forms—but nature always has a few tricks left up her sleeves. Yet, despite centuries and millennia of inspecting birds and beetles and ferns and fossils, it wasn’t until the late 20th century that we discovered the oldest form of life on Earth.

Obviously, animals and plants and fungi are quite easy to see with the naked eye, and bacteria and protists are more readily available for study, but less than 30 years ago, humans realized that there was an entirely new group of organisms on the planet – a third domain of life!

Recommended Video for you:

What Is Archaea?

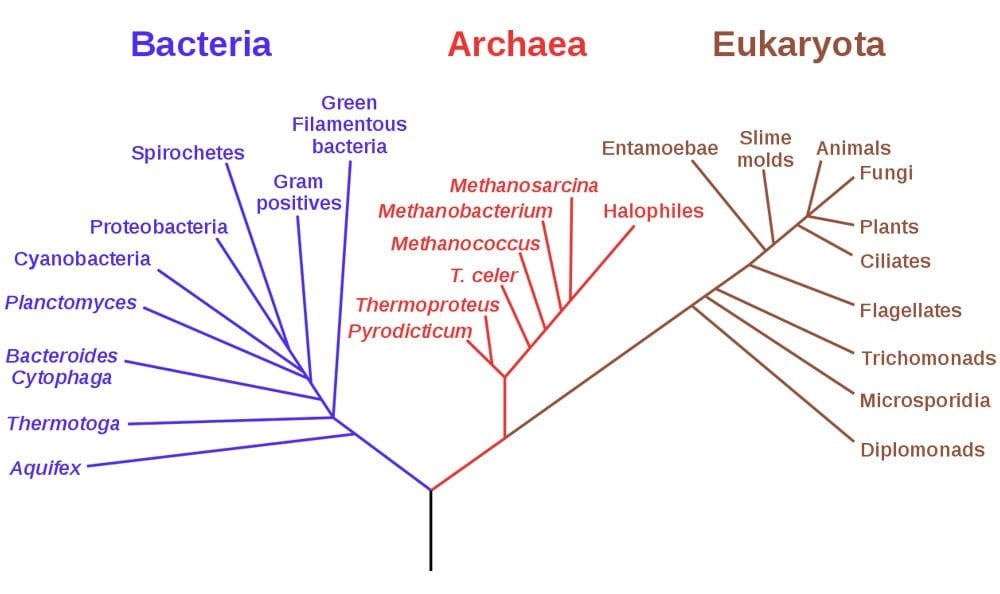

Archaea is the third domain of life—”domain” being the highest categorization level of life on the planet. There are two other domains, Eukaryota and Bacteria, but they are also relatively “new”. Before the 1990s, kingdom was the highest classification of life, in which all organisms were divided up into animals, plants, protists, fungi, bacteria and archaea.

However, as technology and curiosity continued to progress, researchers made an interesting discovery. While life had previously been believed to have arisen in two distinct paths—prokaryotes (bacteria) and eukaryotes (all other multicellular organisms)—some prokaryotes were found to be very dissimilar to bacteria. It soon became clear that there were, in fact, three distinct paths of life on earth that followed our universal common ancestor.

Eukaryotes and Bacteria only told part of the story; it wasn’t until the rise of genetic sequencing and comparison, in place of the simple analysis of morphology, that a clear third branch of life became obvious. The pioneer of this theory, Carl Woese, dedicated a good chunk of his life to the research and arguing of this idea, but his breakthrough was dismissed for years. He had discovered a third form of life that contained more than 200 species of some of the strangest and most extreme organisms we have ever discovered.

Why Were Archea Discovered So Late?

As has been the case throughout human history, shifting paradigms in the scientific world can be a difficult and frustrating task. Carl Woese and his research was ignored for more than a decade, but scientific thinkers of the past would often die long before their ideas were reexamined and eventually praised. Not only that, but the taxonomic system based on kingdoms had been in place for more than 200 years, since the groundbreaking work of Carl Linnaeus. Upending such a universally accepted system was no easy task, particularly because we lacked the technology to take a closer look.

Once researchers were able to make use of DNA sequencing and could read the genetic code of an organism, our ability to identify patterns and nuances was greatly improved. Even though many of these species were right under our noses, and already identified, they had been incorrectly categorized as a form of bacteria, and that simply wasn’t the case.

Once researchers were able to make use of DNA sequencing and could read the genetic code of an organism, our ability to identify patterns and nuances was greatly improved. Even though many of these species were right under our noses, and already identified, they had been incorrectly categorized as a form of bacteria, and that simply wasn’t the case.

What Makes Archaea Special?

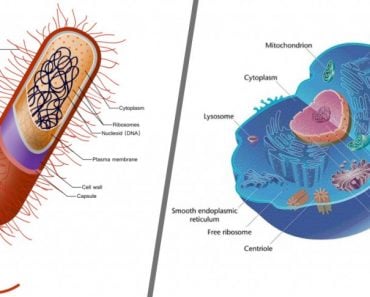

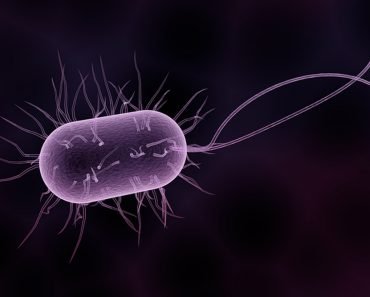

When it comes to microscopic life forms, many people struggle to see the differences, even if they are fundamental variations. In terms of Archaea, as mentioned, these are single-celled organisms that are similar in size and shape to bacteria, hence the initial confusion in their classification. However, once you look closer, the differences become much more apparent.

Archaea microbes have certain characteristics that are more in line with eukaryotes than bacteria, such as more complex enzymes for replication, as well as unique components in their cell membranes. They reproduce asexually, and can use sunlight or carbon as an energy source. However, their range of potential sustenance is also far broader than other species, enabling them to survive and thrive in some of the harshest and most unlivable ecosystems on earth. They can feed on metal and ammonia, as well as natural gas and basic sugars; this flexibility and diversity within such a small range of species is one of the fascinating elements of these well-hidden organisms.

Surviving extreme temperatures, pressures and chemical exposure, these organisms are the epitome of survivors, and can be found thousands of meters down living on hydrothermal events, as well as in glaciers and volcanic hot springs. These microbes have gained a rather cool name as a result of their intense lifestyles—extremophiles. Depending on what sort of extreme environment they thrive in, they possess different names, e.g., thermophiles, radio-resistant microbes, halophiles, among others.

Aside from their undeniably unique morphology and abilities, Archaea are also important because of their place in the history of life. Most researchers believe that some of the species we still see today may have been around during the most tumultuous and destructive periods on Earth, when life had to survive in savage (or extreme) conditions of heat and atmospheric shifts. These early forms of microbial life provide a picture into the past, and fill out our understanding of where we came from.

Furthermore, these microbes aren’t simply relegated to volcanoes and the bottom of the ocean, although those varieties do get the most attention. You can also find these microbes in your own body! There is a type of extremophile called methanogens, which live in our digestive tract, and help to eliminate waste products of digestion by converting it into methane.

A Final Word

Despite their presence in every human being, and in some of the most awe-inspiring places on Earth, we have only been studying this domain of life for two decades. Researchers are eager to scratch past the surface of this new branch of existence and reveal even more secrets about our origins, our present, and even our potential for survival among the stars!

References (click to expand)

- Woese, C. R., Magrum, L. J., & Fox, G. E. (1978, September). Archaebacteria. Journal of Molecular Evolution. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Spang, A., Caceres, E. F., & Ettema, T. J. G. (2017, August 11). Genomic exploration of the diversity, ecology, and evolution of the archaeal domain of life. Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).