Table of Contents (click to expand)

In the simplest form, Murphy’s Law states “what can go wrong will go wrong”. Technically speaking, it’s not a law, but rather a “quote-turned-maxim”.

You have probably experienced moments of misery countless times. The day you leave your house without an umbrella, it starts to rain heavily. You buy a rising stock, but it rapidly starts to fall. You go to the bathroom, and your phone starts ringing from the other room. You try to get your favorite drink from a vending machine, and the can gets stuck.

When you drop a slice of buttered toast, it always seems to falls with the butter side down. You may think that the whole world in some eerie ways is conspiring to make mockery of you, demean you, and defeat you.

Guess what? One of the alleged laws of our world perfectly captures this travesty—Murphy’s Law. Although there are a few variations to it, the most famous phrasing is “What can go wrong will go wrong.”

Recommended Video for you:

Not Exactly A Law

The interesting part of Murphy’s Law is that it’s not a law in a true sense! Instead, it is a popular quote that has become a maxim. Murphy’s Law is often jokingly called the fourth law of thermodynamics. Some even call it the inverse of the Midas touch!

So how was this unusual law discovered, and why it is so popular?

Where Did Murphy’s Law Come From?

The aerospace industry is where work is done in a harsh, unforgiving environment. Though you might not believe it, that is where Murphy’s Law was born.

MX981 Project And The Testing Of G

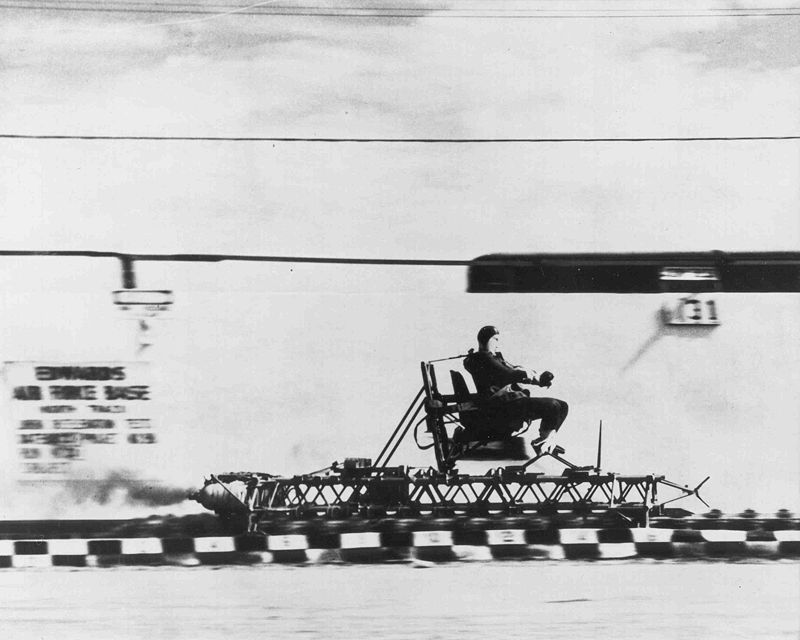

In 1949, officers at Edwards Air Force Base in California performed experiments as a part of the MX981 project. The project was intended to assess the human response during a rapid deacceleration. Experiments were conducted to simulate and understand the impact of an airplane crash on our physiology.

In the initial stages, officers tied dummies to the rocket sled. This rocket sled accelerated up to 1000 kilometers per hour and then abruptly halted. However, the officers weren’t convinced with results based on dummies. They felt that having an actual human as a test subject would give more reliable results.

Colonel Stapp, who was part of this project, took on the challenge. He agreed to get himself tied up in place of a dummy and endure rapid deacceleration. The Air Force captain, Edward Murphy, was assigned the responsibility of designing the harness to strap around Colonel Stapp.

The final design submitted by Murphy’s harness had 16 sensors to measure G forces (gravitational forces) acting on the subject (Colonel Stapp). There were two ways in which each of these 16 sensors could be configured. One was right, and the other was wrong.

After tying Colonel Stapp to the rocket sled, the rocket sled took off. The team suddenly stopped the rocket sled once it reached 40 G. Under 1G, we would weigh around 70 kg on average, but under 40 Gs, we weigh 40 times more—about 2800 kg.

So, the 40G shift was an enormous amount of acceleration that the gutsy Colonel Stapp had to endure as part of the experiment. After the experiment, he survived with a concussion and bleeding from several bodily orifices.

As luck would have it, despite enduring this gruesome ride, the sensors didn’t register any readings! Colonel Stapp immediately called Edward Murphy to see what had gone wrong.

Murphy’s Law At Play: All 16 Sensors Were Configured Wrong!

After careful inspection, Edward Murphy realized that every single sensor of the total 16 sensors was configured incorrectly. Not even one was in the right configuration! Captain Murphy was dejected, and pointing towards the technician (who had configured the sensors), said in a derogatory tone, “If there are two ways to do something, and one of those ways will result in disaster, he’ll do it that way.” This was the original form of Murphy’s Law.

After this incident, Murphy went back to Wright Airfield, where he was stationed, but Colonel Stapp, the man known for his flamboyance, was impressed by Murphy’s proclamation. In a press conference soon after, Colonel Stapp gave encouraging remarks about the rocket sled experiments. He said they had taken into account ‘Murphy’s Law’ and were therefore able to ensure the highest safety standards. When asked what ‘Murphy’s Law’ was, Stapp condensed the original version as “Whatever can go wrong will go wrong.”

This condensed or misquoted version of Murphy’s proclamation was picked up as Murphy’s Law by the media and was soon being talked about and used beyond the aerospace circle.

Proliferation Of Murphy’s Law

Murphy’s Law and its variations have been collected in numerous books and websites. Several bands are named after Murphy’s Law, and it was even mentioned in Christopher Nolan’s movie, Interstellar. In the movie, while explaining Murphy’s Law to her daughter, the protagonist Cooper gives a more positive spin to Murphy’s law and says, “Whatever can happen will happen.”

Murphy wasn’t the first to realize this supposed perversity of fate. In the eighteenth century, famous Scottish poet, Robert Burns, wrote that the best laid schemes of mice and men oft go awry. In the nineteenth century, Rudyard Kipling supposedly first observed that no matter how many times you drop a slice of bread with butter, it will always end up with butter side facing the ground. These are all subtle manifestations of Murphy’s Law.

Is Murphy’s Law Real?

So, is Murphy’s Law actually true? Not really. In 1996, scientist Robert Matthews proved that a few commonly cited examples to support Murphy’s Law, like the landing pattern of buttered bread are not about bad luck, but physics. In his paper, Tumbling toast, Murphy’s Law and the fundamental constants, he explained why physics is behind the butter side falling to the ground. He demonstrated how adding butter to the bread shifts the center of gravity, making the buttered-sided bread face the ground.

Selective Memory And Negative Bias

Another reason why people acquiesce to Murphy’s Law is that it plugs into our inherent negativity bias and selective memory. We tend to remember unwanted things that happened to us and focus on them much more than on those things that went in our favor. Basically, anything that goes bad is likely to linger in our minds much longer than the things that went right.

Illusory Correlation

Matthews also talked about something called “illusory correlation”, which is why people believe in Murphy’s Law. Illusory correlation is when a person wrongly sees a relation between two variables, when in reality no such relation exists. These two variables can be a person, action, idea, or event. For example, when we are in a traffic jam, we always get the feeling that we’re in the slowest lane. This faulty presumption stems from our inherent behavior. We focus more on cars going past us than pay attention to ourselves going past other cars.

David Hand, statistician and professor of mathematics at Imperial College London, reckoned that the law of truly large numbers should make Murphy’s Law occasionally turn true. Additionally, selection bias would ensure that those occurrences would linger in our minds for longer, giving the sense that Murphy’s Law is universal, when that’s not really the case.

Offshoots Of Murphy’s Law

Although Murphy’s Law might not be 100% correct when scientifically tested, it occasionally turns out to be true. Murphy’s Law captures a jaded and pessimistic view of the world very well, which is why it’s so popular.

Since its popularization following the remark by Colonel Stapp, astute thinkers have provided some interesting spins to the original Murphy’s Law and have come up with their own versions. In fact, there have been hundreds of offshoots to Murphy’s Law that have found their way into books and websites. We’ll conclude this article by looking at some of those witty offshoots:

- Nothing is as easy as it looks.

- Left to themselves, things tend to go from bad to worse.

- You always find something in the last place you look.

- A good plan today is better than a perfect plan tomorrow.

- You never find a key until you replace the lock.

- Matter will be damaged in direct proportion to its value.

- Those who can, do. Those who cannot, teach.

References (click to expand)

- (2001) Project MX-981: John Paul Stapp and Deceleration Research. The United States National Library of Medicine

- Matthews, R. A. J. (1995, July 18). Tumbling toast, Murphy's Law and the fundamental constants. European Journal of Physics. IOP Publishing.

- Murphy's law | UCL Science blog. University College London

- Matthews, R. A. J. (1995, July 18). Tumbling toast, Murphy's Law and the fundamental constants. European Journal of Physics. IOP Publishing.

- Murphy's Laws - Cheap Thoughts. Angelo State University