Table of Contents (click to expand)

Quantum entanglement is a strange phenomenon of the universe in which two subatomic particles are linked together such that when one particle is changed, the other particle is also changed, even if the two particles are separated by large distances. This inexplicable phenomena came to be known as “Quantum entanglement”, a term originally coined by Erwin Schrödinger, another early adopter and theorist of the quantum world.

Have you ever tried to solve a mystery of the universe? The task seems rather daunting, but there are plenty of scientists and researchers that have spent their lives trying to find answers to the most paradoxical questions of existence.

Einstein is credited with unraveling some of these fantastic mysteries, but there is one strange phenomena of the world that even the great Albert Einstein felt stumped by. He was so baffled that he gave it a decidedly unscientific name – “spooky action at a distance”.

If Einstein couldn’t figure it out, I don’t know how much luck we’ll have trying to explain it, but this bizarre phenomena of the universe, more commonly called “quantum entanglement” is far too interesting to ignore.

Recommended Video for you:

The Tiny World Around Us

Try to imagine the smallest thing you can hold in your hand and still see with your eyes. A grain of sand works well for this example. Now, that may be a single grain of sand, but it likely contains about 50 quintillion atoms (yes, 50 million million million atoms). The brain’s ability to comprehend the atomic scale is quite limited, but we’re going to dig even deeper.

Within those 50 quintillion atoms, there is a deeper level of subatomic particles that weren’t even discovered until 1897, when electrons were first named. In the century or so since then, we have discovered more than a dozen other types of subatomic particles, including quarks, mesons, gravitons, neutrinos, and other names that seem pulled from the pages of a science fiction book.

Some of these subatomic particles are “elementary”, meaning that they can’t be broken down any further, while others are composite, meaning that they are composed of multiple subatomic particles. This latter category is what fascinates particle physicists and the operators at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC).

These particles were eagerly studied by researchers across the world, but it was seen that the traditional laws of Newtonian physics didn’t always apply in the subatomic world, so a new school of thought was required. An entirely new branch of physics (Quantum physics) was developed to create a framework in which these subatomic particles could be understood.

The Subatomic Particle Paradox

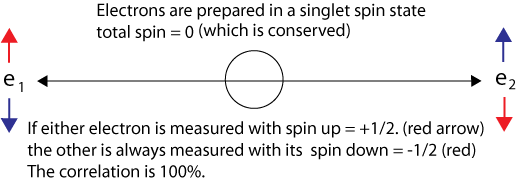

Now, we can measure subatomic particles based on certain pieces of information regarding their location in space-time. The most useful piece of information is “spin”, which is defined by the particle’s angular momentum. This spin isn’t “observable” per se, because this data is only acquired through packets of subatomic energy that can be measured (and thus a quantum number is assigned). Now, a subatomic particle can’t change the speed at which it rotates, but it can change the direction.

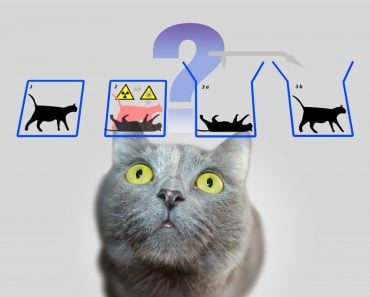

The quantum world operates on the idea of probability states, commonly known as superposition, which means that these particles exist in every state at the same time, at least until a researcher tries to measure it. Ironically, when it is measured, the waveform collapses and the spin can be measured.

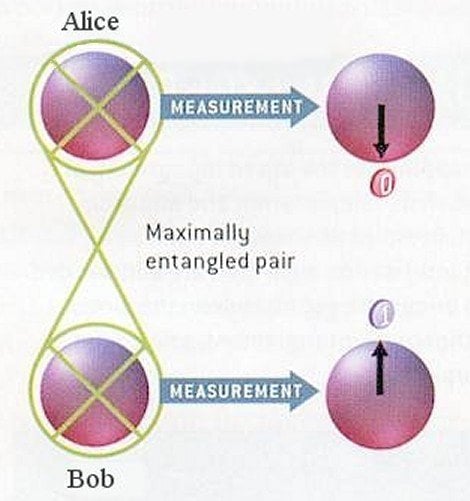

Now, let’s consider a simple subatomic particle: a photon. Before this photon is measured, it is in a superposition spinning in all directions at once (remember, quantum physics is weird….). It’s possible to split a photon into two photons by shining a light through the proper medium, and at that point, you’ll have two photons in superposition. When you measure one of those two particles, the strangest thing happens… they both fall out of waveform, like Alice and Bob below.

Now, remember that quantum number that was mentioned earlier? Let’s assume that the original photon has a spin value of zero. When you divide it into two photons, the two will spin in opposite directions, maintaining the neutral state of zero. If you reverse the spin of one photon, the other will also reverse.

The paradox that stumped Einstein is that this change happens instantaneously. Even at that impossibly small scale, information must still be transferred, either through light, energy, waves etc., but that wasn’t the case. The two subatomic particles were linked somehow, and changing one would instantaneously change the other, even if the two particles were separated by large distances.

This inexplicable phenomena came to be known as “Quantum entanglement”, a term originally coined by Erwin Schrödinger, another early adopter and theorist of the quantum world.

Given that nothing in the universe can move faster than the speed of light, and this “instantaneous” change of spin states revealed a transfer of information thousands of times faster than the “universal speed limit”, the greatest minds of the century were genuinely stumped.

Is There Any Explanation For Quantum Entanglement?

Theoretically, even if these particles were separated by millions of light-years, they would still instantaneously counter one another’s movements, locked in their eternal connection across the cosmos. Thus far, the furthest distance two entangled particles have been is roughly 1.5 miles, but there are exciting plans to launch an entangled particle to the International Space Station (roughly 220 miles) and determine if its entangled particle partner back on Earth will continue this “spooky action at a distance”.

The entire concept has been bending minds for decades, because it breaks one of the most fundamental laws of the universe. The information transfer between the two particles cannot occur faster than the speed of light, and yet it does.

These tangled particles are not limited to pairs either; a study in 2014 artificially entangled approximately 500,000 particles, suggesting a particle cloud “group brain” that instantaneously reacts when any single component is measured or altered.

Taking this a step further, into the macrocosmic scale, let’s talk about the Big Bang, which was essentially the moment when the entire universe exploded from a single particle and began expanding (and hasn’t stopped since!). Given what we just learned about the strange nature of entangled particles, there could be entangled particles spread across the universe. Every single particle could be entangled with another, or a large group!

There could be billions of particles that are inherently linked through quantum entanglement, which means that some insignificant spin shift that we stimulate on Earth may have a subatomic result on the dark side of the Moon, or the other end of the galaxy!

Bitter Brainiacs

Scientists don’t like paradoxes that they can’t solve, so in response to quantum entanglement, Einstein and his friends stated that the quantum theory was “incomplete” and that some inherent concept or material was missing. Subsequent “loopholes” attempting to explain the strange facts of quantum entanglement were developed by Schrodinger, Einstein, and other theoretical physicists, as though they simply couldn’t admit not knowing the answer. These loopholes have most been disproven in the past six decades, but that “spooky action at a distance” still remains.

To this day, we don’t fully understand quantum entanglement, nor the hidden mysteries of the quantum world, but with possible applications like quantum computing and a unified Internet of entangled particles (both of which could change the world as we know it), researchers are not giving up any time soon.