Table of Contents (click to expand)

The plant species to which “poison ivy” belongs produces a defensive toxic plant oil called urushiol. Poison ivy makes this oil to prevent pesky herbivores from feeding on its leaves.

Poison ivy is truly every camper’s nightmare. This innocent-looking plant packs an itchy punch that “leaves” you appreciating just how good your skin was before you touched it.

Growing up, you may have seen cartoons or movies that showed just how irritating poison ivy and other members of that plant family can be. I first saw its scary effects when Malcolm from “Malcolm in the Middle” wiped his face and tears with poison oak after a heartbreaking talk with Laurie. His face looked decidedly awful after that.

What makes poison ivy so harmful? And why does the rash build up sneakily without us realizing?

Recommended Video for you:

What Is Poison Ivy?

Poison ivy and its relatives—poison oak and poison sumac—belong to the genus Toxicodendron. These plants are commonly found across the United States, except for Alaska and Hawaii. They are also present in smaller concentrations on other continents.

Poison ivy grows as a vine that spreads through grassy areas. It can even grow in shrubs in colder climates, and the leaves grow in groups of three, although some forms have their leaves in groups of 5 or more. Such variation in their appearance can depend on the location and the weather.

Poison ivy’s dangers were first documented in 1609, when English explorer John Smith first wrote about his experience. He was the explorer who established the first English settlement in Jamestown, Virginia.

The exact words he used to describe poison ivy were, “The poisonous weed, being in shape but little different from our English ivie; but being touched causeth reddness, itchings, and lastly blysters, the which howsoever, after a while they pass away of themselves without further harme; yet because for the time they are somewhat painefull, and in aspect dangerous, it hath gotten itselfe an ill name, although questionless of noe very ill nature.”

Why Does Poison Ivy Cause A Rash?

The plant family gets its name ‘Toxicdodendron’ because they produce a defensive toxic plant oil called urushiol. Poison ivy makes this oil to prevent pesky herbivores from feeding on its leaves.

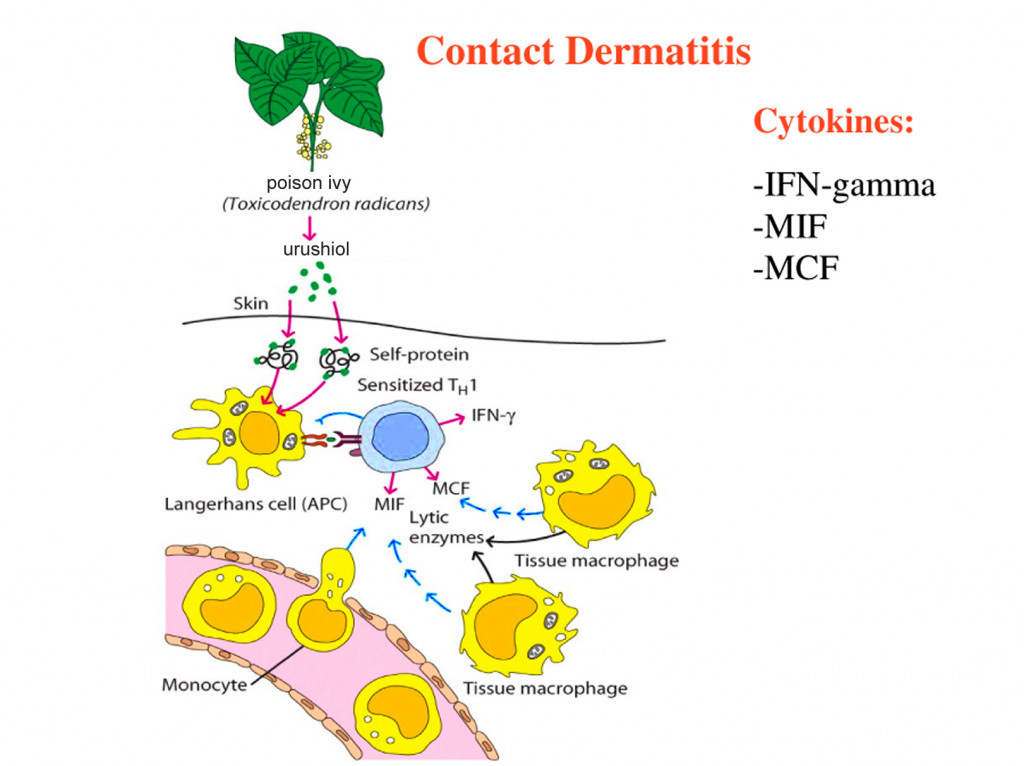

When the leaves touch us, urushiol seeps into the skin. It then reacts with certain skin proteins and immune cells, thus causing inflammation, a.k.a. the rash.

Direct contact with poison ivy isn’t the only risk when it comes to these plants. The oil can spread through contact with other surfaces too. If a dog comes in contact with the plant and the oil ends up on its fur, petting the dog can allow urushiol to spread from the dog to your hand!

In medical terms, this rash is called contact dermatitis. It’s used to describe anything that causes skin swelling after physical contact. It’s quite common in the United States due to poison ivy’s prevalence. One early study in the 1950s thought that poison ivy was the most troublesome North American plant, as so many people would catch rashes after unintentionally touching it. Poison ivy-induced contact dermatitis is still common in North America and affects around 50 million Americans every year.

Interestingly enough, the rash won’t form immediately after exposure to urushiol. In fact, it can take 1-3 days to develop.

Why Does It Take Time For The Rash To Form?

This is where things get tricky. The reason poison ivy is so dangerous is that urushiol is an allergen, and almost everyone is allergic to it. Around 85% of Americans are allergic to urushiol, leaving very few lucky enough to be unbothered by it.

That’s not all. The rash won’t form after first contact with urushiol, but being exposed to urushiol a second time and onwards will cause a rash, with each subsequent exposure capable of causing a worse rash.

This is because touching poison ivy causes a specific immune response in our body called a delayed hypersensitivity reaction. It’s called this because of the body’s delayed response to the allergen’s exposure and the severity of the tissue damage.

When urushiol enters the body through the skin, it binds to proteins in the skin and forms complexes. These urushiol-skin protein complexes are recognized by our immune cells as foreign entities and are subsequently cleared out. Such immune cells include antigen-presenting cells and T helper cells. Their function is to alert our body’s immune system when foreign toxins and germs enter our body. They function as border patrol units that protect our bodies from foreign invaders.

The first time urushiol enters the skin, our immune cells recognize the urushiol-skin protein complexes as something new and calmly breaks them down.

Now, our body’s immune system is incredibly intelligent and has a wonderful memory capable of remembering nearly all the germs or toxins it encounters. Unfortunately, that’s a disadvantage in the case of poison ivy. The second time urushiol penetrates the skin, these immune cells recognize these complexes and think they are facing another invasion.

To show their authority, the immune cells launch a far more aggressive response, including the T helper cells making signaling molecules called cytokines. The cytokines are interferon-γ, macrophage-chemotactic factor and migration-inhibition factor. Cytokines signal for reinforcements, leading other immune cells, such as macrophages, to come and join the fight.

Macrophages release some protein-breaking enzymes called lytic enzymes that break down the urushiol-skin protein complexes. These enzymes are harsh and do a lot of collateral damage to the tissue surrounding the urushiol contact site. Et voila! We have our iconic poison ivy rash.

This immune response takes time to gear up, so the rash can take anywhere between a few hours to 3 days to form. It depends on how quick your body responds to urushiol.

Sadly, each time we touch poison ivy, the series of unfortunate events is repeated, and each time our body launches a more aggressive response. So, even if you don’t have a bad reaction to poison ivy the first time, repeated exposures can eventually lead to worse reactions.

Conclusion

There is no specific treatment for contact dermatitis. The best way to fight it is to avoid it entirely. Stay clear of Toxicodendron plants. If you come in contact with it, quickly washing the contact point with soap and water can remove the urushiol. However, this is most useful if done within the first 5 minutes.

You can try applying calamine lotion to soothe a rash, but if it gets really bad, contact your doctor for stronger prescription creams that will ease the pain.

However, we don’t see the rash until it’s already too late. By that point, our body has already launched its defensive approach and the damage has already begun. Basically, next time you go hiking in the woods, be more aware of where your feet tread!

References (click to expand)

- KLIGMAN, A. M. (1958, February 1). Poison Ivy (Rhus) Dermatitis. A.M.A. Archives of Dermatology. American Medical Association (AMA).

- Poison ivy, oak, and sumac: How to treat the rash. The American Academy of Dermatology

- (2022) Type IV Hypersensitivity Reaction - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. The National Center for Biotechnology Information

- Poison Ivy: an Exaggerated Immune Response to Nothing Much. The University of Massachusetts Amherst

- Symes, W. F., & Dawson, C. R. (1954, June). Poison Ivy “Urushiol”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. American Chemical Society (ACS).

- Kalish, R. S., & Askenase, P. W. (1999, February). Molecular mechanisms of CD8+ T cell–mediated delayed hypersensitivity: Implications for allergies, asthma, and autoimmunity. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Elsevier BV.

- Poison Ivy, Sumac and Oak - American Skin Association. americanskin.org

- Poison Ivy: Prevention Takes Priority | URMC Newsroom. The University of Rochester Medical Center

- Goldsby, R. A., Kindt, T. J., Kuby, J.,& Barbara A. O. (2002). Immunology, Fifth Edition. W. H. Freeman