Table of Contents (click to expand)

Merit is not the only factor that drives success in life. Social identities and access to resources also play a big role in achieving success.

One often hears the word ‘meritocracy’ tossed around in conversations about success. Meritocracy is used to refer to a government, and more broadly a society, where those people who get greater opportunities receive them based on their merit and capacity. The perception of merit allows us to think of education and opportunity as a palatable reassurance that we will be given equal opportunities as any other, with overall conditions being irrelevant to the allotment. It also allows what is best to thrive in the pool of talent in a given society.

Recommended Video for you:

Is Merit A Social Construct?

A social construct is a broad term used to refer to any concept or phenomenon that exists because of the subjective social interactions to which we are all party, instead of some objective criterion. So, can we question if merit as a concept is socially constructed?

The answer seems to be yes and no.

If we see merit as both a proclivity and talent for something, then there may be some inherent aspects to it as a concept (someone’s voice may be suited to singing and they may like to sing, so they hone this skill).

However, if we see it as a more abstract quality of being worthy of an opportunity by virtue of that proclivity and talent, then this ‘worth’ aspect is definitely socially constructed.

Certain kinds of talents and goods in society are considered more ‘worthy’ than others due to subjective perception of their value. How a society creates a hierarchy is dependent on the needs it prioritizes and the rewards that are given upon fulfilling those needs. This is why some parents would prefer for their children to be engineers or doctors, rather than musicians or artists.

Arguments For A Merit-based Arrangement

There are some obvious pros to a merit-based society and arguments for how it has the most potential among all other current options to secure success. Merit minimizes the unfair influences of personal relationships on opportunities. Nepotism, for example, is when you promote your own family over other equally or more meritorious candidates.

Merit-based advancement also allows for the success of the society as a whole, due to greater growth, innovation and economic and technological advancement within it, by incentivizing better solutions to existing alternatives.

Hypothetically, merit-based arrangements allow for individuals of all classes and circumstances to achieve great things in life, unencumbered by class, caste, race, sex and other variables.

Does Merit Truly Guarantee Success To All Equally?

For merit to truly guarantee success to one and all, irrespective of situation and circumstance, it would have to possess no acquired aspect to it. This is to say that one would have to be born with merit and it could not be affected by one’s living conditions.

All singers who make it to the top, in such a case, would be born with the requisite skills necessary to launch themselves in the music industry, without any training (essentially eliminating the need for voice coaches).

This would counter the effect of social, economic, political and environmental factors on the growth of a person’s merit.

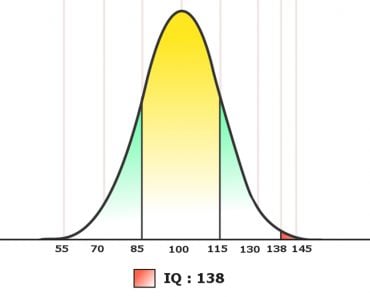

The assumption that merit exists independently of other socio-economic factors is unrealistic. If merit were stagnant, talent would never be improved upon and skills would never be gained in later stages of life. However, we see through personal example and that of others, that raw capabilities can be worked upon, and with the right effort, honed and expanded over time. To achieve the latter, access to resources is an essential catalyst.

To take a simple example that illustrates this, the highly gifted child of a blue-collar worker and the precocious child of the CEO of a multi-national company will not get the same kind of exposure and opportunities. Even if they both start off with the same merit, the former might have to travel every day to get training, while the latter might just be able to hire a private tutor.

Such a disparity can be seen across multiple facets of one’s environment, such as one’s race, religion, health status and more. These, however, are micro-level factors. There may also be macro-factors, i.e., factors that operate not at an individual level, but at a large-scale region or institutional level.

For example, certain state institutions might play a role in alienating sheer merit from success. The lack of good public educational facilities would automatically put those meritorious students who cannot afford a private school at a disadvantage. Similarly, in a state where women are not allowed to get a university education or join the workforce, meritorious women will be worse off than men, in general.

Arguably, there is an obvious solution to this. If merit can be accurately judged through curated tests, then such tests could be made in a manner that cannot be prepared for. However, this is a naïve view of testing that, when done periodically, will rely on certain patterns that can be anticipated and practiced.

Conclusion

The social and economic environment in which merit is cultivated affects the very nature of that merit in complex ways. Merit transcends the individual and relies on the how, where and even when of the individual’s existence. By acknowledging that merit is not the only thing that matters in the race of success, we can save ourselves some of the negativity that the stress of competition imposes on our lives.