Table of Contents (click to expand)

Legend says that excess wealth brings greater downfall. Modern economics calls this the Paradox of Plenty.

It is a common conception that places like Venezuela and the Middle East are incredibly wealthy. With such a huge amount of oil under their soil, it’s almost like God blessed them with wealth and good fortune, right?

Wrong. In fact, even Africa, despite being home to the second-largest rainforest, has been unable to use this resource satisfactorily for the growth of its nations. We call this the Resource Curse or the Paradox of Plenty in real-world economics, or the curse of Montezuma, which is popularly known in Mexico as “Traveller’s diarrhea”.

Legend says that the ninth Aztec emperor, Montezuma II, put a curse on the Spanish soldiers invading Mexico. Montezuma built an empire with an incredible amount of gold, and some subjects mistook their leaders as Gods themselves. After all the good Montezuma had done for Spain, he was kidnapped and murdered for his gold by conquistadors, and Montezuma’s curse was born. Spain fell in the late 16th century, owing to the same gold that they treasured so much.

The myth of Montezuma’s curse might not have caused Spain to fall, but its hunger for resources certainly did.

However, that was long ago. The real question stands… are resource-rich countries still cursed with the Paradox of Plenty, aka, the Curse of Montezuma?

Recommended Video for you:

Economic Development From Abundance

Economic development is an important goal for every country, and it always begins with a simple question: Why are some countries poor and others rich? Is it a difference in human effort, natural resources, cultural influence, climate, history of invasions, or pure luck?

It is tempting to conclude that some countries started working on their economy earlier, giving them the first spot in the race. If that were correct, Russia should be the most developed, since they were the first to introduce national planning with 5-year plans, strategizing growth techniques for the country to foster economic, social and educational development.

However, Switzerland ranked highest in HDI in 2022.

GDP per capita growth is not the only measurement of a country’s development. Largely, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) uses HDI (Human Development Index) to differentiate between less developed and more developed countries. It calculates how well a country is performing using life expectancy, quality of education, and GDP growth.

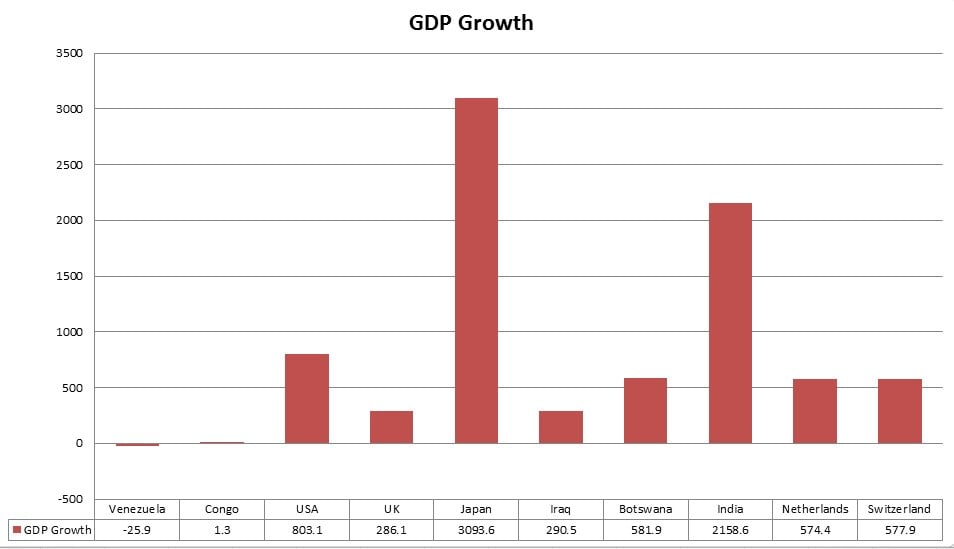

However, it’s the rising per capita GDP that ultimately fosters human development, leading to investment in health and educational institutions. Here is a graph of GDP growth percentage comparison between a few countries. Since 1960, countries like Japan, India, and the USA have expanded their GDPs, while Venezuela fell due to its political and economic instability.

GDP growth of countries 1960-2021 (based on constant 2010 USD: USD adjusted for purchasing power of people in 2010)

If we begin at the root of the problem, it is a country’s resources that form its building blocks, as they drive economic development through rising per capita income and improved standards of living.

The Paradox Of Plenty: Real Or Myth?

Some resource-abundant countries have had a comparatively slower growth rate (measured in per capita income in the country) than resource-poor countries since the 1960s. We also measure growth/development in terms of education and health, since income alone does not determine one’s ‘quality of life’. Having an excess of one resource also cannot guarantee that the country will progress faster. In many cases, an excess of a single resource has caused a negative trend, leading to a drop in per capita GDP, rather than an increase (Dutch disease).

Venezuela, Iraq, Angola, and the Democratic Republic of Congo had all the oil, diamonds, and essential resources to build their country with gold. However, processing these primary raw materials is insufficient as a driver for economic development.

When a country focuses on a single over-exploited resource, their expertise and growth in other sectors slow down. They might capture a portion of the export market to bring in money for the country, but their efforts and investments are drained into a single sector. A lack of diversification in the income sources of a country often causes the “Dutch disease”.

The Dutch Disease: Real-world Examples

Angola is a popular example of both these concepts, due to its rich diamond and oil reserves. 90% of its exports and wealth rely on these specific areas. One expects a country with so many diamonds to be sitting on riches, but Angola has experienced widespread poverty, huge income and wealth gaps, political problems, corruption, and huge fluctuations in oil prices. The “paradox of plenty” works together with the Dutch disease to showcase how countries in the modern world, despite having the building blocks of development, are unable to put it into action.

Another interesting example is Botswana, where we see a positive Dutch disease impact.

Botswana, like Angola, has diamonds as an abundant mineral. Before discovering diamonds there in the 1970s, their economy mainly depended on agriculture. Dragging themselves out of poverty, the government started making policies for overall development and promoted infrastructural, educational, and other developmental efforts.

These examples show how, in the modern world, the paradox of plenty is tied not only to resources, but also to other connecting sectors that influence the utility of a resource.

A Walk Through Time

Throughout history, we have seen kingdoms, emperors, and people of all sorts invade and loot one another. We called it ‘conquering’ or building an empire back then, but mostly, they were doing it for the resources.

Before the exact definition of the resource curse, we had the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis (1950), which has since been updated with a modern-day thesis. They discovered that countries rich in natural resources are involved in producing and exporting primary goods (raw materials), while industry-supported countries specialize in manufacturing.

The Prebisch-Singer hypothesis was later modified because it had two problems. Firstly, modern reports show that not all resource-abundant countries need to rely on exporting primary products, and even if they do, it doesn’t necessarily mean they would face a slow growth rate. Secondly, exporting primary goods can actually be beneficial during some economic periods.

More scholars weighed in to show how the primary sector depends on linkages with multiple progressive sectors in the economy. We can link to industries for inputs (backward linkage), or industries that prepare primary resources to be an input for other products (forward linkage). Now that an economy can diversify, it can specialize too, in terms of development. However, historical studies show that instead of development, a country can also fall into the Staple Trap, by exporting and exhausting its staple resource.

In 1982, Peter Neary and Max Corden wrote about the ‘Dutch disease’ after observing the sharp economic decline of the Netherlands, Australia and Norway (along with some members of OPEC).

Results

Coming back to the same point, the paradox of plenty does not necessarily imply that countries with abundant resources will specifically export primary goods and suffer the negative impact of the Dutch disease. Although they are interlinked, these concepts are applicable in different countries in different ways. Some can benefit greatly from whatever key resource they have, while others might fail to do well, even with abundance.

The main advantage of studying the paradox is understanding how we can classify different degrees of developing and developed countries that still suffer from Montezuma’s curse. With this classification, we can apply developmental policies in these countries and significantly reduce the inequality gap, helping countries extricate themselves from a low-income trap.

References (click to expand)

- A Leibbrandt. (2017) Does the Paradox of Plenty Exist? Experimental Evidence .... City of Monash

- V Polterovich. (2010) Resource abundance: A curse or blessing?. Sion In South Sudan (Unmiss)

- Szalai László - Montezuma's Revenge.

- Book : Resource Abundance and Economic ... - UNU-WIDER.

- Measures of Economic Development.