Table of Contents (click to expand)

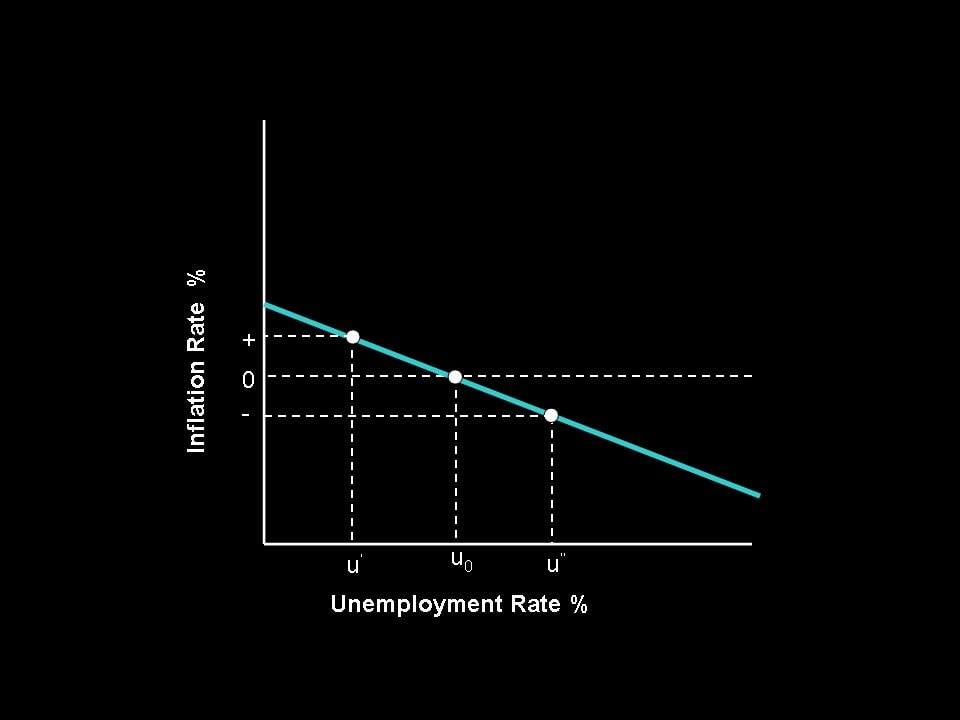

Looking at how inflation and unemployment move in opposite directions through the short-run Phillips Curve reveals some interesting results.

The Phillips curve is an economic theory that has been around for more than half a century. According to this theory, in the short-run, inflation and unemployment follow an inverse relationship. However, in the long haul, this tradeoff between the rate of inflation and unemployment does not hold.

The Phillips curve is therefore one of the most contested economic models in history. There are people for it, and there are others against it. Hailed as “probably the single most important macroeconomic relationship”, what exactly is the Phillips Curve? And by corollary, does inflation really bring down unemployment?

Let’s delve deeper.

Recommended Video for you:

Inflation And Unemployment

Inflation is basically an economy-wide price rise. We say that there is inflation if the current prices are higher than the previous year’s prices. Inflation is the difference between the two price levels.

Unemployment is basically joblessness. To be more technical, if someone wants to be employed and is actively looking for a job, but cannot manage to find one, we say that they are unemployed.

Policymakers want to reduce inflation, and they want more people employed at the same time. However, historical data suggests that you can only have one of them. Unemployment often acts as the price of low inflation.

Thus, the association between unemployment and inflation can be explained using the Phillips Curve.

The Phillips Curve

Alban William Phillips was a British economist born in New Zealand. In 1958, Phillips wrote an article in the Economica, titled “The Relationship between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wages in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957,” which started this entire discussion. He explained how wage inflation had caused the unemployment rate to fall.

The modern-day Phillips curve—reworked by the economists who came after Phillip—tries to identify the relationship between price inflation (price rise) and unemployment.

Others like Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps included more elements, such as supply shocks (short supply making things expensive), in the modern Phillips curve.

How Does The Philips Curve Work?

Here is how the Phillips Curve works. Let’s assume that there is inflation in the economy. Since the prices of all commodities are high, firms will look to produce more. Companies would then be able to sell what they make at a higher price (which could hopefully mean a higher profit).

However, in order to expand their output, the companies would need help, so firms across the economy would hire more people. When a lot of firms do this, the unemployment rate falls. Thus, the price rise would lead to more people having a job. Thus, just like the Phillips Curve predicts, higher inflation would mean lower unemployment.

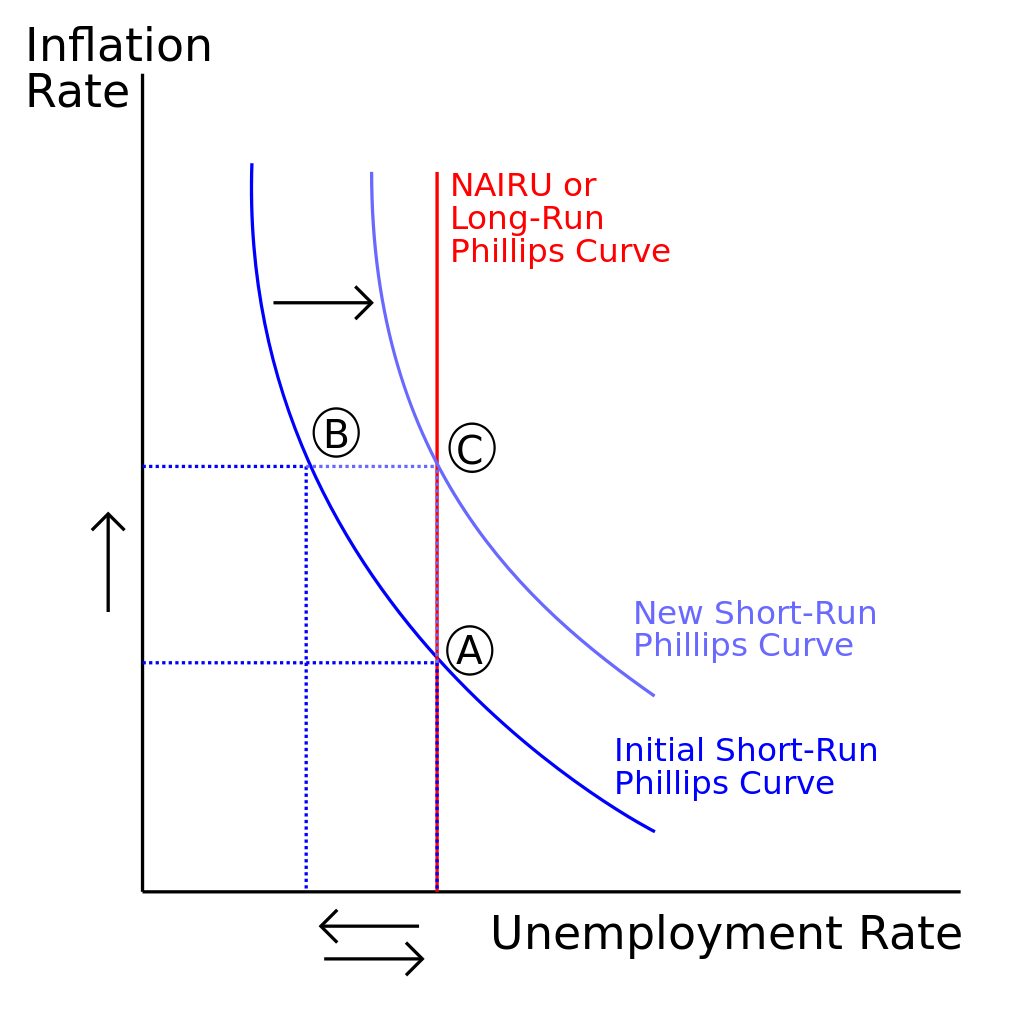

The Long-Run Phillips Curve

However, here’s the catch: the Phillips curve works only in the short run. Over time, people realize that even though the prices of everything they can buy in the economy has increased, their pay hasn’t increased. Therefore, people will push for higher wages so they can keep buying the same things that they’ve always bought. Firms would have no choice but to cave in to the demands of their employees.

This is where things take a turn. When companies pay higher wages, their cost of production increases. Subsequently, producers let some of their workers go, and unemployment would return to its previous level. Unfortunately, the overall prices in the economy or the rate of inflation would remain the same, at the new higher level.

Thus, over a long period, a price rise can’t increase employment, so inflation can only reduce unemployment in the short run.

Through the Phillips Curve, we can see, graphically, how unemployment and inflation move in opposite directions. However, as mentioned, this trade-off only happens in the short run. In the long run, the Phillips Curve becomes vertical at the economy’s natural rate of unemployment (NAIRU).

Looking At The Data

According to American economists Samuelson and Solow, policymakers can take advantage of this tradeoff. Firstly, they can choose a combination of inflation and unemployment figures on the Phillips curve. Later, they can use monetary and fiscal policies to achieve that desired level.

For instance, in the US, during the 1960s, policymakers managed to increase employment by boosting the money supply and creating an inflationary situation. Since the money supply increased, meaning that people had more money in their hands, the demand for goods and services also surged. A higher aggregate demand spurred an increase in production, and subsequently an increase in employment.

Similarly, in the 80s, the US government tried to bring inflation to heel by contracting the money supply through monetary policy. Just as the Phillips curve predicts, this lower inflation and reduced aggregate demand caused many people to lose their jobs. However, thanks to rising unemployment, the inflation rate subsequently fell to 3%.

In both these cases, inflation decreased unemployment in the economy. In the first case, inflation caused unemployment to fall, and in the second case (the 1980s), unemployment pulled down inflation. In other words, during both the 1960s and 1980s, the relationship explained by the Phillips Curve held strong.

Conclusion

The Phillips Curve is broadly applicable. It works not just in the US, but also in the other economies around the globe. However, the theory has received its fair share of criticisms as well. A paper published by Stock and Watson in 2008 suggests that Phillips Curve forecasts are relatively good, but are often irregular. The stagflation of the 1970s, mentioned earlier, shows that in the long run, inflation and unemployment do not exhibit a negative relationship.

Now, let’s get back to the answer to our original question. Does inflation bring down unemployment?

Yes, to an extent. Terms and conditions apply!