Table of Contents (click to expand)

Tableau vivant refers to a theatrical and artistic genre that consists of creating static scenes populated by real actors or models, often based on historical events or artistic works.

If you’ve ever walked through Times Square in New York City, or strolled along Southbank in London, you likely remember the buskers dotting the street corners, many of them heavily costumed and covered in makeup. My personal favorites are the frozen statues, performers who will often stand for minutes at a stretch without moving a muscle, only to spring into action when an unsuspecting passer-by comes too close.

While you may recall seeing such performers in the past, you may not know that they are the latest iteration of a long tradition that dates back to the Middle Ages. Such spray-painted street entertainers are engaging in tableau vivant, even if they don’t know it!

Recommended Video for you:

History Of Tableau Vivant

Back in the medieval era, a Christian mass (religious ceremony) would often end with a series of dramatic scenes portrayed by actors or religious figures. And this tradition continued outside the religious sphere for parades, coronations, and other large-scale events. Traditionally, the figures would arrange themselves against a carefully coordinated backdrop or scene and then stand completely still, as though they were figures in a painting. The costumes, lighting, scene design, makeup, poses and actors’ expressions were of critical importance to the tableau vivant being deemed a success.

Golden Age Of Tableau Vivant

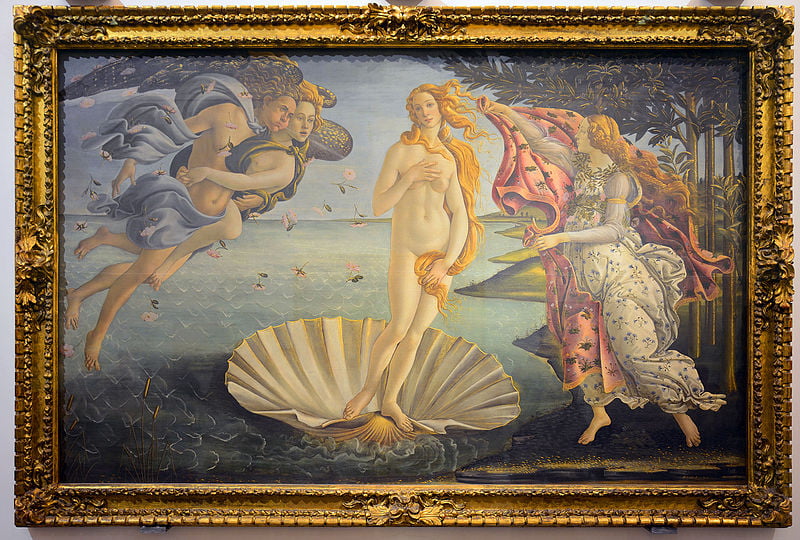

As a genre of performance and visual art, tableau vivant had its golden age in the 19th century, before the advent of film and television began to dominate people’s attention; tableau vivant could be staged at any scale or level of detail, which made it a remarkably flexible and popular pastime, though it has traditionally been associated with more elite or wealthy levels of society. The scenes depicted in tableau vivant commonly drew from religious texts, classical mythology, and military history, as well as visual art from around the world, moments of literature and scenes from everyday life.

Prior to this era of globalization, ease of travel and accessibility to fine art (via the Internet), many people had no way of seeing the great artistic masterworks of the Renaissance and other eras. Tableau vivant enabled vibrant, informative and engaging artistic experiences for audiences before the age of accurate color reproduction and mass media. These “living pictures” could be staged anywhere, in someone’s living room on a low budget, or they could be featured as the feature entertainment for a royal wedding. In more formal spaces, the performers might have struck their pose on what looked like an actual canvas, as large wooden frames could be erected around the border of the stage.

This specialized genre of entertainment took on many forms, and served many purposes. From celebrating the return of Napoleon’s conquering army to honoring the birth of Jesus Christ in a community theatre nativity play, this unusual style of performance has withstood the test of time.

The Sexualized Side Of Tableau Vivant

The popularity of this art form may also be explained by its close link to nudity, censorship, and sexuality. In the depiction of many classic art scenes (i.e., the Birth of Venus) or moments of religious history (i.e., Adam and Eve), the nude form simply cannot be avoided. That being said, in the 19th century, there were strict censorship laws in Europe and America regarding female nudity on stage, specifically when it came to moving. Essentially, tableaux vivant represented an interesting loophole where a love of aesthetic beauty crossed with a more base desire to witness the nude female form in public.

Pose Plastique

A related subset of tableau vivant is “pose plastique”, in which a performer would take on the pose of a statue, typically classical and nude in nature. As opposed to being a part of a larger scene, this more individual form of performance is the origin of those disturbingly still robot men busking for coins near modern-day tourist traps!

Due to the perceived illicit nature of this performance (in some parts of the world), these statuesque ladies were occasionally relegated to frontier towns and sideshows, as such revealing performances had fewer tolerant venues in major cities. London and New York theaters, notably, featured such tableaux in numerous variety shows throughout the early 20th century, including the legendary and notoriously risqué Ziegfeld Follies.

Tableau Vivant In The Modern Age

Though it was primarily a theatrical form at first, when photography and film entered the media landscape of humanity, tableau vivant had new avenues to be captured and enjoyed. Elaborate stagings of historical events with dozens or even hundreds of participants could now be arranged and captured for mass distribution, unlike the transient nature of consuming a tableau vivant in “real life”.

The ability to permanently capture a tableau vivant and disseminate the image added a new layer of depth to this genre; this led to more social commentary through the work, such as staging the scene of a classic work of art, but changing some of the details to send a strong political, cultural or social message. In the 20th century, the inherent function of tableau vivant expanded from entertainment; the form was adopted by protesters from disadvantaged and oppressed groups, as well as used in comedic or satiric fashion to comment on the work of other artists or time periods.

A Final Word

One could argue about the “purpose” of art until the end of time without reaching a resolution, but there is no denying that for an art form to survive, it must evolve. In the case of tableau vivant as a widespread art form, its heyday may have been in the 19th century, but the philosophy and impact of this genre remains relevant. We see remnants and descendants of this style all around us, from dress-up photograph booths to flashmob performances. There is something inherently powerful in imitation, and tableaux vivant allows viewers and participants to more deeply engage with other times and places.

References (click to expand)

- Tableaux Vivant: History and Practice - Art Museum Teaching. artmuseumteaching.com

- Chapman, M. (1996). 'Living Pictures': Women and Tableaux Vivants in Nineteenth-Century American Fiction and Culture. Wide Angle. Project Muse.

- Reynolds, R. E. (2000). The Drama of Medieval Liturgical Processions. Revue de musicologie. JSTOR.

- Martin, R. (2006, November). Toward a Kinesthetics of Protest. Social Identities. Informa UK Limited.