Table of Contents (click to expand)

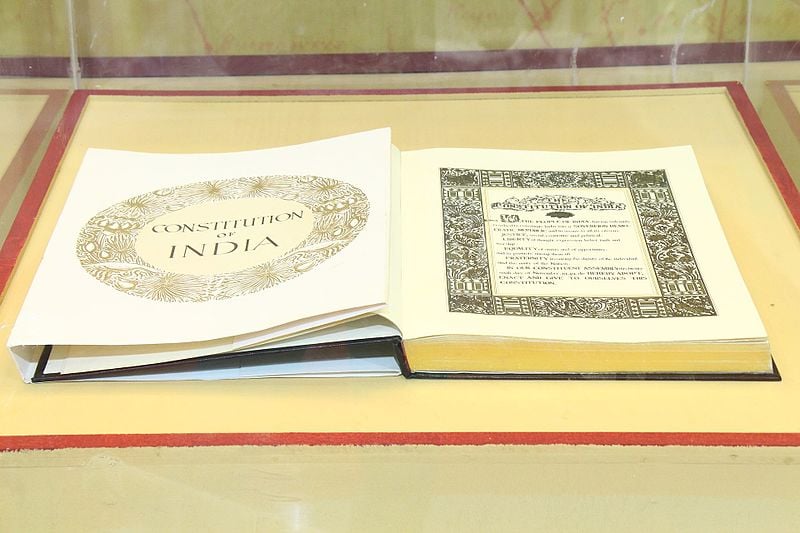

The concept of rights precedes constitutions, which codify the aspirations of their makers in how the specified rights will manifest.

Constitutions are seen as the pinnacle and hallmark of democracy—no matter how autocratic a state may be in action, its claims of possessing a democratic nature and motivation always start at and stem from a constitution. Constitutions are also where citizens locate their claims towards the state and other entities and individuals in the form of rights.

Recommended Video for you:

Defining The Scope Of Rights

Rights are a set of entitlements or claims that individuals possess. These can be claimed by virtue of being a citizen (or subject), or by virtue of being a human being, depending on the school of thought one subscribes to.

Based on such a classification, rights can be broadly categorized under two heads—positivist or natural.

The concept of rights has evolved over time, with a marked shift from religious rights to legal rights in most jurisdictions. With different cultures and societies, the extent of recognizing this shift and prioritizing different types of rights varies. Some rely heavily on what is codified as law to legislate, while others give equal, if not more, significance to religious dicta and customary practices.

Natural Rights Versus Positivist Rights

In jurisprudence, or the study and philosophy of law, natural rights are those that are considered to be inalienable and inherent to human beings, and should be available to all, despite the conditions of their existence based on some notion of morality or divine bestowal. They are viewed as fundamental principles that underlie moral and legal systems, and are used to protect and promote individual autonomy, dignity, and well-being.

Examples of natural rights include the right to life and liberty, which is believed to be available to any person, even if no legal guarantee for it exists.

Positivist rights, on the other hand, are rights that are specifically created and defined by a particular legal system or government. They are codified in laws, policies, regulations and treaties, and can vary depending on each legal system or jurisdiction. Quite often, they use natural rights as a starting point. Positivist rights would then include the right to healthcare and the right to education, both of which, it can be argued, stem from the right to lead a dignified and fulfilled life.

Which Came First?

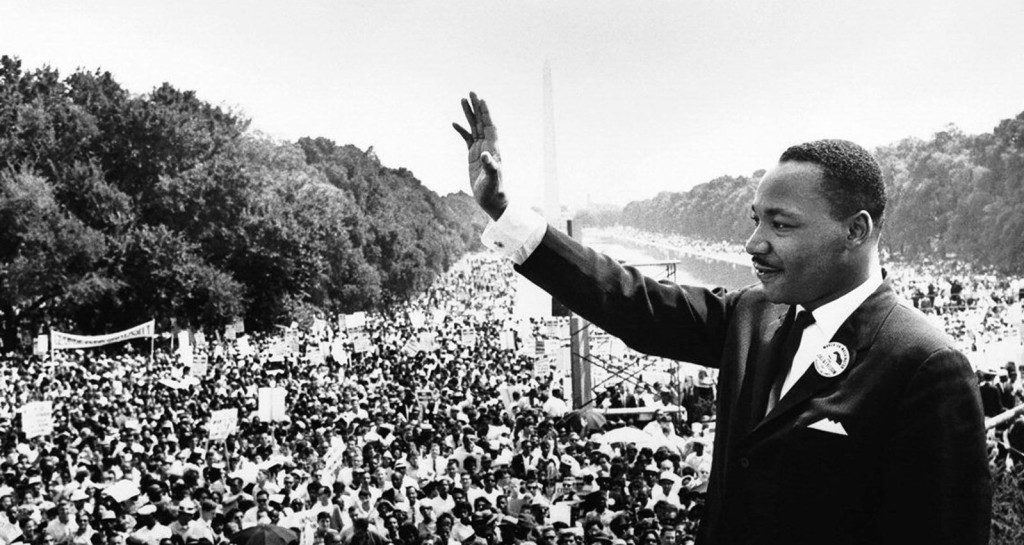

Rights existed before Constitutions, in a sense. Even before democracies became the norm of governance, monarchs granted certain rights to people, depending on the historical context of their reign. The granting of rights by monarchs, however, was often limited and did not extend to all people in society (mostly to aristocratic classes and the clergy).

It was not until the development of modern democracies (ancient democracies were notably hierarchical) and the recognition of universal human rights that individual rights were extended to all members of society, regardless of social status or class. If you believe that there are natural rights, based in the social mores and morality of the times, then the mainstreamed concept of universal human rights existed long before constitutions.

Natural rights do not flow from the government, but from the collective perception of what it means to be human. Cultures all over the world have values that they grant to their members as rights, even if a sovereign does not command that the people have such claims. Constitutions then become legal frameworks that codify pre-existing rights to legitimize citizens’ claims in a manner suited to the acknowledgement of the state and its administration.

The state and administration, through the recognition and protection of natural rights, have asserted their need and legitimacy, and have thus developed legal systems and political institutions. This is best illustrated by the English Magna Carta, signed in 1215 CE, which established certain rights and freedoms for the English nobility and paved the way for the development of modern constitutionalism.

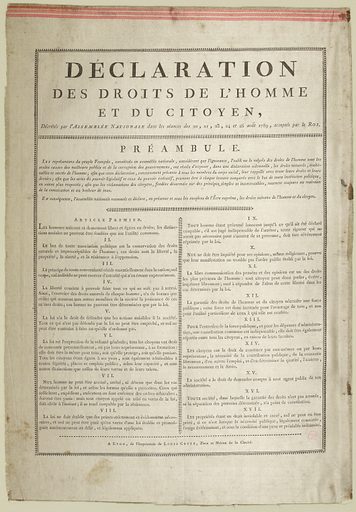

It is perhaps also in this vein that the French Revolution, despite not having had a constitution to back its claims against the monarchy, through the sheer strength of a shared lived experience of oppression, was able to proclaim liberty for the French across a wide breadth of social status.

It was only after the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (which later became the preamble of the 1791 Constitution) that the process of constitution-making began.

Conclusion

The recognition and protection of rights has been a fundamental concern for societies throughout history, albeit more often in a collective sense, instead of through the lens of individuality (a more modern development). The preservation of cultural and religious traditions has been made possible across generations because of this collective recognition.

While certain ideas of rights seem to exist before constitutions, not all of them do. It is here that we must be cautious… can we extend a right back in time to be a universal ideal when the society that created a classification (preventing it from being universal) did not see it as an ideal to be extended to all? From a contemporary audience’s perspective, women have deserved the right to vote for as long as voting has existed, but most nations in the past had a long struggle with acknowledging, accepting and enabling this right.

The question of which came first—rights or constitutions—depends on the reader’s perception of who gave the rights (a sovereign or the nature of humanity) and whether rights truly exist in practice, or only in theory.

References (click to expand)

- FI Michelman. (2003) The constitution, social rights, and liberal political justification. Oxford University Press

- MJ Perry. THE CONSTITUTION, THE COURTS AND HUMAN .... CORE

- https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/flr69§ion=66&casa_token=w2Fi42_OgBIAAAAA:equ9CxeCQODSe1RP4k7WF4VAUJy8sUUx1NR0xjQNYtviiZwp06tk819wb3ALji-ZbU2RJF_U

- Dippel, H. (2005). Modern constitutionalism, An introduction to a history in need of writing. Tijdschrift voor Rechtsgeschiedenis / Revue d'Histoire du Droit / The Legal History Review. Brill.

- https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/237108