Schadenfreude is the pleasure that we feel when we see others suffer. It manifests itself when we feel envy, aggression or believe that the misfortune was somehow deserved.

We humans are blessed with a beautiful range of emotions. What is special about us is that we not only feel our own emotions, but are also capable of understanding the emotions of the people around us. We feel happy for the neighborhood kid who scored well on his exams, we feel excited when our friend breaks the news of her pregnancy, we feel sad when someone we know loses a loved one, and so on. In short, we are capable of actually feeling what others feel; it’s almost as if we absorb their emotions!

We usually feel bad when we see other people suffering. However, we’re not always virtuous or compassionate beings. Instead of feeling bad about other people’s suffering, we sometimes feel delighted about it. However, there’s no reason to worry; this is just Schadenfreude at work!

Recommended Video for you:

What Does Schadenfreude Mean?

Schadenfreude (shaa-duhn-froy-duh), which literally translates from German as ‘harm-joy’, is the strange pleasure that we experience in response to another person’s misfortune.

People all around the world experience schadenfreude. In fact, this uncanny warm glow upon seeing others in distress dates back to the time of Aristotle, who termed it epichairekakia. The French call it the joie maligne, or the ‘cunning joy’, the Dutch speak of leedvermaak, and an old Japanese proverb says that the misfortune of others tastes like honey!

Although gloating has often been compared to schadenfreude, it’s not quite the same. While gloating conveys a more active participation of the ‘gloater’ in the misfortune of the gloated, schadenfreude is felt when a third party is responsible for the misfortune.

In fact, this is what makes schadenfreude so illegitimate in the eyes of Friedrich Nietzsche, a German philosopher. It is not an earned joy; it is the pleasure derived not by ‘making’ someone suffer, but by simply ‘watching’ them suffer.

Does this mean that we’re all monsters consumed by giddy, malignant joy?

No, certainly not.

We never wish bad things for our loved ones, and we do empathize with those less fortunate than us, so… What makes us feel schadenfreude sometimes?

Schadenfreude manifests itself in three subforms- justice, rivalry and aggression.

Deservingness Theory Of Schadenfreude

According to psychologist N.T. Feather, schadenfreude is primarily justice-based. He believes that we take joy in seeing another person suffer if we perceive their suffering to be deserved. Whether we like to admit it or not, we’re all guilty of smiling a bit when a coworker we dislike misses a deadline!

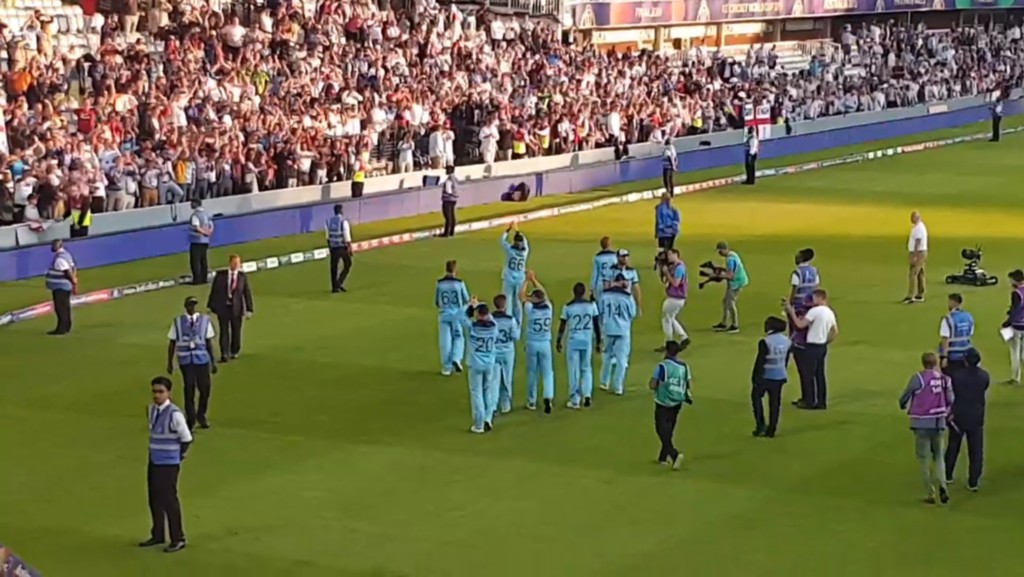

The cricket world very recently experienced this form of schadenfreude. The World Cup Finals 2019 saw England win against New Zealand in a rather controversial game. Although both teams posted the same total on the scoreboard, England was awarded the Cup because they hit more boundaries in their innings. The entire world felt sorry for the resilient New Zealand team and its unfair loss. Therefore, when England lost the Ashes to Australia on their home ground just a month later, it seemed well deserved to many.

Studies have shown that the tendency of judging the social character of a victim starts as early as one’s infancy. In a controlled study, infants witnessed a puppet trying to climb a steep incline. On some attempts, another puppet helped it move up, while on other attempts, a third puppet hampered its efforts by pushing it downhill. Infants as young as three months were found to prefer the prosocial puppet—that helped the puppet climb—rather than the antisocial one that hampered the puppet’s efforts. In another related study, most eight-month olds liked a puppet that in turn harmed the ‘bad puppet’ (Source).

However, one’s perception of others’ deservingness may not always be the cause of schadenfreude. Instead, they may experience schadenfreude first and then justify their feelings using deservingness as an excuse. Moreover, there may be situations where the misfortune was not at all perceived to be deserved. So what causes schadenfreude in such cases?

Rivalry-Based Schadenfreude

Much like justice-based schadenfreude, rivalry-based schadenfreude also relates to social comparison. The difference, however, lies in the person’s focus: while justice-based schadenfreude focuses on an appraisal of the sufferer’s misfortune, rivalry-based schadenfreude depends on one’s evaluation of their own social status.

In other words, this theory links schadenfreude with another human emotion—envy. Envy is a negative emotion; it is an uncomfortable feeling that makes us feel inferior to the envied person. When the envied person experiences a downfall or disappointment, it makes them less enviable in our eyes, thereby reducing our negative feeling of envy and washing us with a sense of relief. A downfall in their social status automatically increases our self-evaluation, which makes us feel good about their misfortune.

Thus, envy creates a conducive environment for schadenfreude.

Inter-Group Theory Of Schadenfreude

The competition between groups can often get more intense than the competition between individuals. The best example that comes to mind when we talk about group rivalry is sports. The aggression between rival teams and their fans can turn even the best of friends into bickering belligerents!

Now, it definitely makes sense that a rival team losing to our favorite team would make us happy, because it means a win for our team and the pride of having defeated the rival. However, inter-group aggression makes us grin with schadenfreude even when the rival team loses against another team, in which case there is absolutely no benefit to us. The amount of schadenfreude we feel upon seeing a rival team lose depends on the amount of aggression between the teams and the degree of loyalty within the team.

Schadenfreude can be understood better through other examples, which can be seen as extensions of the aforementioned subforms of justice, rivalry and aggression.

One of the most common situations when we feel schadenfreude is when we see a hypocritical person get his “just desserts”. We experience great pleasure in watching others get exposed, more so when they get caught doing something that they had criticized others for in the past.

Another interesting tendency is schadenfreude directed specifically at the rich…

Tall Poppy Syndrome

The ‘tall poppy syndrome’ manifests itself when the rich suffer a misfortune. Psychologist N.T. Feather reckons that we enjoy the downfall of successful peoples or high achievers more than that of average achievers. “Tall poppies” are a metaphor for the rich, whose success we see as far from normal, similar to a tall poppy that must be cut down, even more so if we believe that their success was not deserved in the first place (Source).

However, the schadenfreude does not only depend on the situations in which we find ourselves. It is a product of that and our personal traits, the most important one being empathy.

Lack Of Empathy

Normally, we respond to another person’s misfortune with empathy. This means that we are genuinely concerned about others, or at the very least, that we understand and sometimes also feel their suffering. We experience distress when seeing others in pain.

Empathetic people help others out of genuine concern or simply in order to reduce their own distress after seeing them suffer. Consequently, a person who lacks empathy feels schadenfreude instead of distress. This is particularly true for people who show high degrees of dark triad traits (Machiavellianism, narcissism and psychopathy).

Insecurity Attachment Styles

Attachment theory suggests that our emotional development happens in the early years of our childhood. Psychologist Mary Ainsworth observed that children either exhibit a secure attachment style or one of the two insecure attachment styles: avoidant style and anxious-ambivalent style.

The quality of the bond we share with our primary caregiver in the early years of our lives not only decides how we feel in our subsequent close relationships, but also forms a basis for social interactions in general. People who are securely attached show trust and empathy in their relationships and have a positive view of themselves and others.

Avoidant people, on the other hand, are emotionally detached and fear intimacy. They lack empathy and prosocial behavior, which, in turn, translates into more schadenfreude. The second insecure style is an interesting one! Anxiously attached people are very sensitive under stressful situations. Since they already have a great amount of personal distress (in the form of anxiety), they usually don’t wish to aggravate it by empathizing with the suffering of another. Therefore, they try to reduce the severity of another’s suffering by simply laughing it off.

In conclusion, schadenfreude, although it seems evil, is a completely natural feeling in most setting. So, the next time you feel happy that your cheating ex just got dumped, enjoy the sensation… you’re not alone!

Meanwhile, it’s time for some schadenfreude, so I’m going to go watch a funny video of clumsy pandas falling down!

References (click to expand)

- (2017) Why Some Take Pleasure in Other People's Pain. The City University of New York

- (2019) Schadenfreude deconstructed and reconstructed. Emory University

- Leach, C. W., Spears, R., Branscombe, N. R., & Doosje, B. (2003). Malicious pleasure: Schadenfreude at the suffering of another group. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. American Psychological Association (APA).

- SURFACE SURFACE - surface.syr.edu