Table of Contents (click to expand)

Reengineering education systems in developing countries requires changes to pedagogical practices. Willingness to make this change is lacking across stakeholders in the system. Providing tangible inputs may not be the solution that developing countries consider.

Dabbling with creative interventions to improve educational outcomes has long been the focus of governments worldwide. Countless policies address issues in education, ranging from increasing enrollment rates to improving skill-based education. Education is the easiest way to improve living standards in the long run. For a country, its human resources are the most prized. What it chooses to do with these human resources determines how other resources will be used.

Improving education has always been a critical focus area, yet why do we still see struggling primary and secondary education statistics across developing countries?

The 2019 Nobel Prize winners, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer, have conducted experiments to determine exactly that.

Reorienting education is a task in developing countries because the focus of schools in South Asian countries, for example, is merely to provide English education under the garb of a modernized curriculum or elite education.

However, there is no way for non-English speaking parents to verify if the teacher speaking in English is even using the correct grammar in public schools, as stated in the book Poor Economics by Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo .

Likewise, governments do not have a mechanism to figure this out. Although the curriculum delivery in English is on paper, the quality is sub-par. This flawed quality deprives students of basic conversational skills because their textbooks are in English, but there is no way for them to understand and relate this to the environment in which they are situated. Furthermore, it hampers their understanding of other subjects.

Kremer and his colleagues experimented to arrive at the above conclusion. The economists distributed grade–appropriate textbooks in English to 25 schools picked randomly in western Kenya. However, the average test scores of students who received textbooks and those who did not were the same!

The experiment conducted by Kremer and his colleagues highlights the fact that providing inputs alone, i.e., textbooks to schools, was not going to help. A change in pedagogical practices in the school must accompany tangible inputs. In some places, just a change in pedagogical practices can make a significant difference, without requiring any other inputs.

The other major challenge facing education in developing nations is a highly demotivated system. Although enrollment rates for primary schools have risen over the years, improved learning outcomes do not necessarily follow.

Parents who send their children to primary school may not let them continue in secondary school, as that child can start earning and contributing to the household income by performing odd jobs. The returns from this sub-par education are not significant.

Additionally, it takes time for education to reap returns, and education is seen as a form of investment; the delayed wait time is not something that every low-income household can afford.

Recommended Video for you:

How Did The Nobel Trio Arrive At Context-specific Answers For Developing Nations?

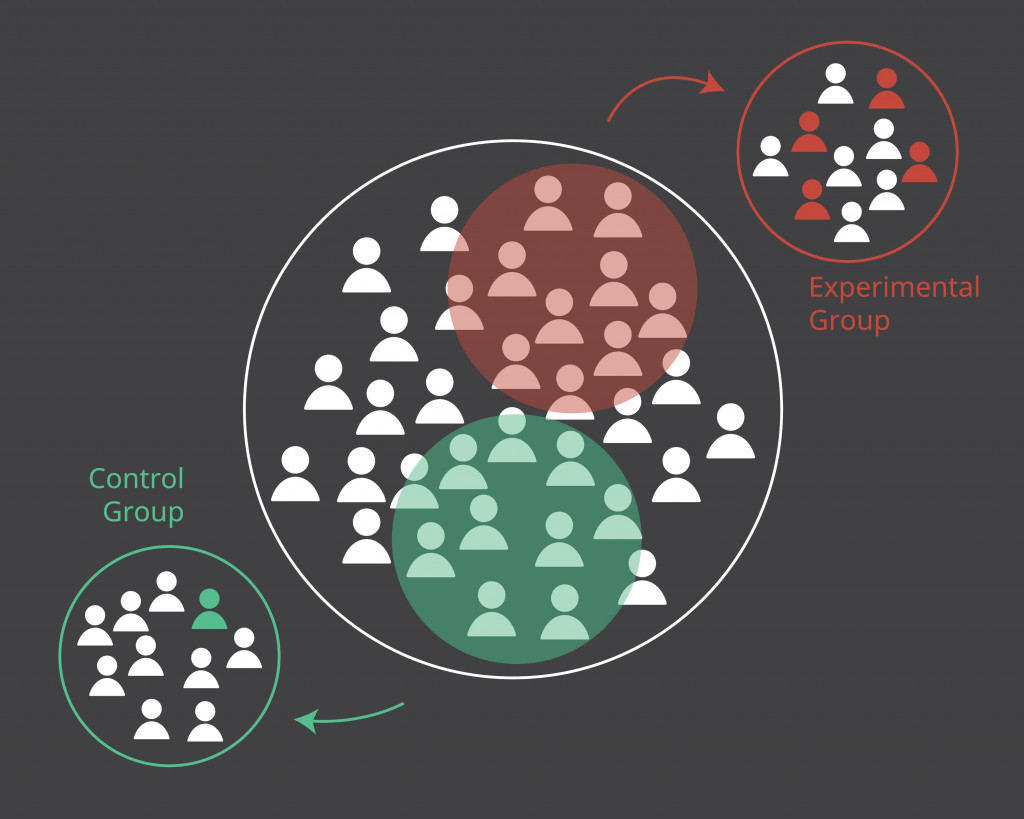

Randomized controlled trials (RCT) is a method that scientists commonly use in a range of fields. Just like the term signifies, two groups are picked randomly. The treatment group is administered a treatment, such as textbooks, while the control group is not given any treatment (textbooks). Over time, the results of both groups are compared to arrive at a causal factor, in this case, whether administering textbooks improves learning outcomes.

This experiment allows researchers to compare the two groups by looking at the impact of the factor that is administered. This control level helps narrow down to one causal factor, rather than being lost in multiple potential variables that affect an issue.

This experimental approach to tackling developmental issues, such as eradicating poverty, improving education, and many others has become the preferred method to arrive at causal factors for a problem.

In the past, economists dealt with long-term solutions, but RCTs identify short-term solutions. The practitioners believe that there is no grand theory or a grand solution to any problem, but by identifying one causal factor, they can design better policy interventions.

Potential Problems With RCT

There is agreement across the board on the need for context-based solutions. However, with RCTs, there are just too many solutions. Even while equalizing two samples, critiques have found that many constraints specific to an individual will be ignored.

For instance, it was found that educational outcomes can be improved through cash transfers, as this was experimented with in Mexico and NY City. Since education is considered an investment, the ministry decided that handing out cash transfers could help eradicate poverty in the long run.

The handout was basically a return for the wages that the child lost while they were at school. The idea was driven to nudge families towards supporting education, regardless of what they thought about its impact. NY City also adopted this idea of a conditional cash transfer, with variations for improving student enrollment.

Although increasing enrollment is the first step, is this solution sustainable? What about pedagogical practices? Incentivizing education in this way may create further problems in terms of finding adequate ways to fund this expense and can erode faith in the system. Should handing out money be the answer?

Will these students eventually be more employable with the skills they learn in this manner? Or do we have to conduct another RCT to figure that out?

It seems rather endless, as has been pointed out by other economists.

The narrowing down to one factor does seem rather unsettling. While it is tempting to locate one causal factor, it is equally possible that various other factors also influence that situation.

Can RCT control for all those factors? In the above example, enrollment has increased through a conditional cash transfer, but what if there aren’t sufficient schools in the locality for students to access? What if a child can earn much more than the cash transfer handed to him at school through odd jobs? Does that mean he must leave school? And most importantly, are we educated merely to earn or learn?

In conclusion, according to RCTs, reengineering education is complex in developing nations due to the medium of instruction being English, while schools lack well-trained English-speaking teachers. Additionally, due to poverty, hunger, and gender bias plaguing these nations, education is expected to reap immediate benefits due to such challenging social conditions.

However, since the returns from education are delayed, children are encouraged to perform odd jobs and supplement the family income, so it becomes difficult to properly assess the impact of educational reforms and advancements.

References (click to expand)

- Banerjee A. V. (2013). Poor Economics: Rethinking Poverty and the Ways to End it. Random House India

- Glewwe, P., Kremer, M., & Moulin, S. (2009, January 1). Many Children Left Behind? Textbooks and Test Scores in Kenya. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. American Economic Association.

- Randomized control trials for development? Three problems. The Brookings Institution