Table of Contents (click to expand)

Venus de Milo may have lost her arms to the ravages of time, war or simple mismanagement by those safekeeping her.

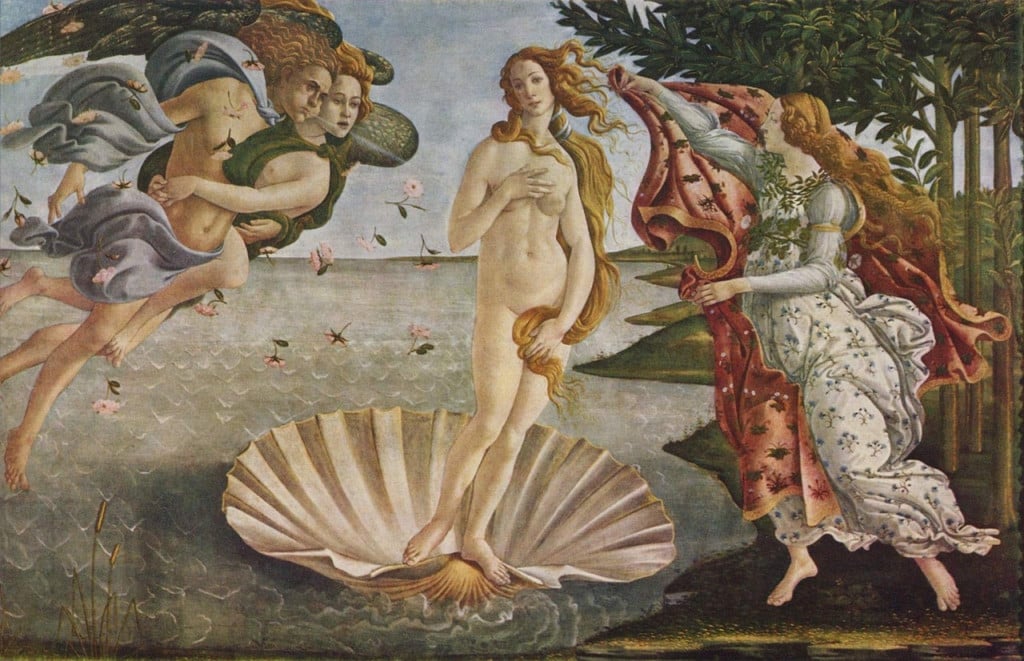

Venus de Milo (literally, Venus—or Aphrodite, as some of you may know her as—of Milos, a depiction of the goddess of love) is one of the most recognized relics from the Hellenistic period. It is an ancient Greek sculpture that is housed along with the Louvre’s other treasures (like the Mona Lisa) in Paris.

It was discovered in 1820 by a Greek farmer and his son (the farmer’s name was Yorgos Kentrotas), in a niche, buried in the ruins of the ancient city of Milos, on the present-day island of… MILOS!

You may have seen the statue or allusions to it in movies and television shows because of the infamous Venus de Milo comedic gag about how she lost her arms…

Recommended Video for you:

What We Know About The Statue

The Hellenistic period of art started with the conquests and end of Alexander the Great’s life and ended with the Roman conquest of the Greeks (though the Romans carried many of this period’s art styles to their own). It is during this time (around 150 BC) that Alexandros of Antioch, the sculptor, gave us Venus de Milo. How do we know that? Well, along with the statue, there was an inscription found that said:

‘Alexandros, son of Menides, citizen of Antioch of Maeander made the statue.’

They don’t display this inscription along with the statue. Perhaps that is because, while presenting it to Louis XVIII, by ditching the inscription that placed the statue in the Hellenistic period, more credibility could be given to it by speculating that the statue was the creation of a Classical (a more revered period for art historians) Greek sculptor Praxiteles. This reasoning, held by those in charge of the Louvre in 1821, carries on to this day.

She was gifted by Charles de Riffardeau, Marquis de Rivière to the French King Louis XVIII, who donated it to the Louvre.

What The Statue Tells Us

The statue mimics the features of an older style, Corinthian, something commonly seen as a marker of the Hellenistic period. Venus de Milo’s figure and drapery point to it being seen and sculpted as something grand and noble. Her 6 meters-long figure is graceful in expression and her poise is reflected on her face.

She was built with two components joined at the hips, which is how she was found, with the upper body and draped legs in separate pieces. Venus de Milo would have been known as Aphrodite to those who built and first laid eyes upon her, but naming the statue Venus was just another way of Romanizing and laying claim to those artworks.

The Lost Arms

If you have some semblance of interest in Greek statuary, you’ll know that they were all made ‘whole’, with limbs and clothes and symbolic accoutrements chiseled from a single piece, often in white marble.

However, given that marble is prone to fracturing, many of the more intricate elements were lost to the ravages of time. This could be one reason why she is missing her arms.

Venus de Milo’s missing arms were broken long before the statue was unearthed for reasons that are largely unknown, despite a wide range of speculation by art historians.

However, there are theories and claims by relatives of the farmer that the statue was dug with at least her left arm holding an apple, though it was detached from the body.

If that is true, it could help substantiate the claim that the woman is actually Venus (it is speculated, given the location, that it could be Amphitrite), given that in the myth of the Trojan War, Aphrodite/Venus was who received the golden apple from Paris, a Trojan prince.

The most popular reason for the arms being missing is a tussle between the French and the Turkish; around the time in the 1820s, there were bands of sailors from both sides fighting for control of it over the shores of Milos, which was under Ottoman control back then. The statue hit the rocks, and thus, lost her arms.

Venus De Milo’s Journey

The fame of Venus de Milo was not always as obvious as it is now. Although it was considered important as an artistic finding from the Hellenistic period, it did not immediately attain its stature as one of the world’s most famous (albeit armless) statues. In the 19th century, when Napoleon Bonaparte lost power in France, in the aftermath of the Napoleonic looting, when France started returning the Louvre’s treasures to their countries of origin, Venus de Milo began gaining her fame.

This is because when Napoleon looted the Venus de Medici from Italy, and the French government returned it, to make up for the hole left behind by one Venus in the Louvre’s collection, they promoted Venus de Milo as a better, more refined replacement.

The propaganda was effective, and Venus de Milo earned the prime spot at the Louvre that she now holds in every visitor’s itinerary.

Conclusion

Venus de Milo may have lost her arms, but her charms live on, very literally for her viewers, but also as a metaphor for love and beauty. That’s why AC/DC gave us their famous line: “She had the face of an angel, smiling with sin. A body of Venus with arms.”

References (click to expand)

- Kousser, R. (2005, April 1). Creating the Past: The Vénus de Milo and the Hellenistic Reception of Classical Greece. American Journal of Archaeology. University of Chicago Press.

- Arenas, A. (2002). Broken: The Venus de Milo. Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics, 9(3), 35–45.

- Lethaby, W. R. (1919, November). The Venus de Milo and the Apollo of Cyrene. The Journal of Hellenic Studies. Cambridge University Press (CUP).