Table of Contents (click to expand)

The French Revolution changed notions of governance, but failed to create a steady republic because of factionalism, external threats and inefficiency.

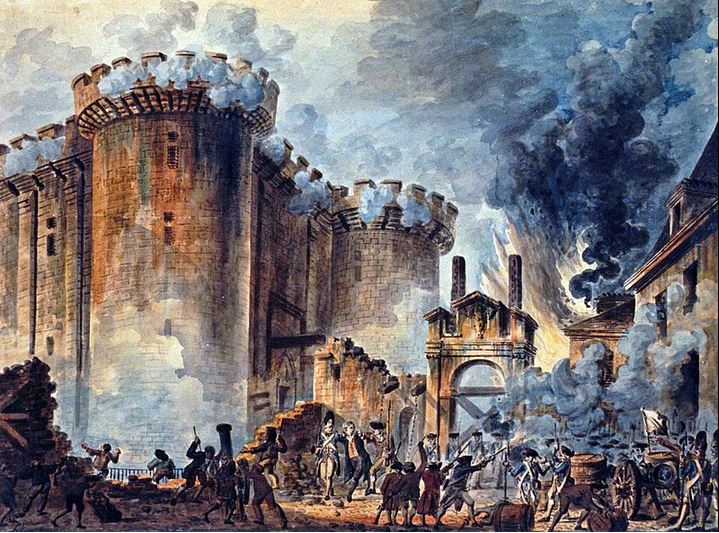

The French Revolution was a period of political and social change and ultimately, upheaval in France that lasted from 1789 to 1799. It was marked by the overthrow of the monarchy and the feudal system, the establishment of a republic, and a very bloody Reign of Terror, during which thousands of people were executed for their political inclinations and social faux pas.

The political landscape of France was drastically altered (for good and for worse) by the Revolution, which only ended with the ascension of Napoleon Bonaparte. Given how one of the most significant consequences of the French Revolution was the abolishment of the monarchy, the relative speed with which the system of governance bounced back to an autocracy (of its own making, perhaps) begs the question — what went wrong?

Recommended Video for you:

The Immediate Cause Of Disillusionment

The Revolution was followed by the Reign of Terror, a period of extreme violence and repression and concomitantly, widespread fear and disillusionment among the French people. The brutal tactics used by the revolutionary government, including mass executions and the suppression of political opposition, were seen as going much too far. This was especially true in rural France, where traditional social structures and religious beliefs were deeply ingrained.

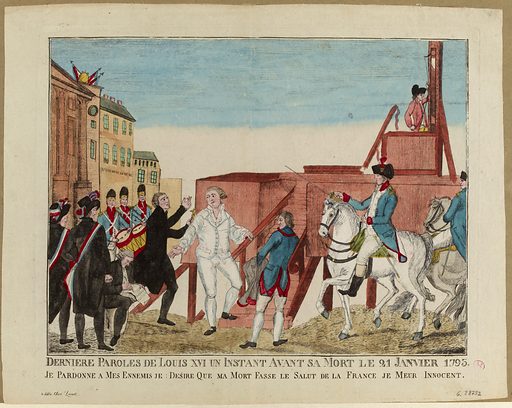

In addition, factionalism within the revolutionaries further weakened them. The Jacobins, who were a radical left-wing faction, supported violent means, like the execution of the king and the Reign of Terror, to achieve their vision of France. On the other hand, the Girondins, who were a more moderate faction, wanted to use democratic and constitutional ways to do so.

The infighting between these factions led to a power struggle within the revolutionary government, with each trying to consolidate their own power, rather than advancing the goals of the revolution. In the process of doing the former, they kept undermining the legitimacy and prowess of the government as a whole.

Along with its inefficiency in curbing discontent and its own workings, the revolutionary government also mismanaged the economy of the nation. The government’s attempts to redistribute wealth and restructure the economy were thwarted by corruption, inefficiency, and resistance from the aristocracy and bourgeoisie.

The Tussle For A Monarchy In France

In the backdrop of the French Revolution, the French countryside had been marred by famines and bad harvests, while the cities suffered shortages of food, especially the staple bread. The dissatisfaction and indignation elicited by the apathy of the monarch, King Louis the XVI, and the Queen, Marie Antoinette, propelled people to support the Revolution, which promised a more sympathetic, pro-people system.

However, after removing the monarchy, the Revolution was marked by a series of external threats by European powers, including Austria, Prussia, and Great Britain, who saw the fall of monarchy in France as both a bad omen and a bad precedent.

The war effort required the government to focus on military and security matters, rather than governance and reform, which had been central to the support it had previously garnered to abolish the monarchy (which had been portrayed as self-centered and indifferent to the interests of the people).

These countries sought to suppress the revolution and restore the old order, and their military responses to France’s internal turmoil further destabilized the country. This limited the government’s ability to focus on internal governance and left space for counter-revolutionary discourses to grow even stronger.

An Ambivalent Tete-a-tete With The Republic

The French Revolution was ultimately brought down by a fundamental lack of consensus among the French people in terms of the governance they sought for the nation. While many people supported the Revolution and its goals of liberty, equality, and fraternity, there was an equally strong conservative lobby who opposed it and were willing to use violence to resist change. This made it difficult for any single group to establish a government that could represent the interests of all French citizens.

While this is an eventuality that all republics and democracies should prepare for in their lifetimes, two things must be kept in mind: one, that the French Revolution was doing something unheard of in feudalist, monarchist Europe (so they really did not have too many examples to learn from); and two, the takeaway from the experiment with the bloodthirsty and remorseless Reign of Terror may have pushed sentiments back towards a familiar form of rule.

Conclusion

While ideas and ideals had fueled the trajectory of the French Revolution, their manifestation left the French wanting for a stable, reliable and strong source of leadership. This is roughly when Napoleon swooped in and declared himself emperor. However, as his military gains were reversed by his own ambitions, the people once more, in the form of the Bourbon King Louis XVIII, turned to the monarchy that had been.

The irony of the situation is compounded by the fact that Louis XVIII ended up accepting and even furthering some of the ideals of the French Revolution by allowing for a greater participatory front by working with the new elites who had emerged during the Revolution, and created a new ruling class that was more representative of the broader population (obviously, he reversed quite a few too, as his reign was still monarchical).

In this way, perhaps, the French Revolution irrevocably changed what governance meant, even as its form reverted back.