Table of Contents (click to expand)

You can distract yourself from pain. Rubbing the skin around the wound or applying an icepack can momentarily relieve you from the pain, but better yet, listening to music or dancing might distract your brain from discomfort entirely.

If you are in pain, try not to focus on it.

This may seem counterintuitive advice, but there is some truth behind it. For example, why does your local physician talks to your child while vaccinating them? And why do you subconsciously rub near a wound or banged elbow to lessen the pain? In fact, even listening to music can help you feel better faster.

There are neurological explanations to this fascinating phenomenon.

Recommended Video for you:

What Is The Gate Theory Of Pain (GTP)?

Pain is a complex phenomenon to study, and much of our understanding of how we feel pain remains shrouded in mystery.

In 1965, psychologist Ronald Melzack and neuroscientist Patrick Wall proposed a new theory for how we feel pain. They called it the gate theory of pain.

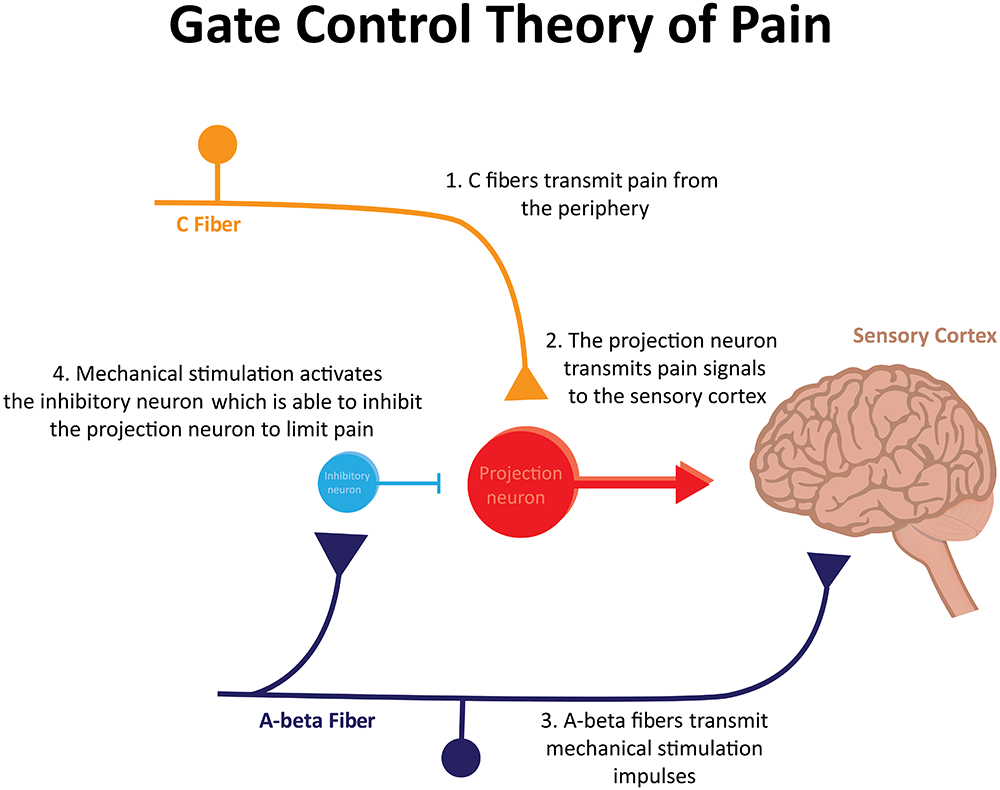

The gate theory of pain describes the mechanisms by which our spinal cord controls the transmission of pain signals to the brain. When the gate is ‘open’, the signal passes to the brain. When the gate is ‘closed’, signals do not travel up to the brain, and the sensation of pain is attenuated.

The interesting bit is that we can “close” the gate by doing certain activities.

To better understand the theory, let’s first try to understand the basics.

How Do We Feel Pain?

Imagine that you are jogging in your local park when you trip and scrape your knee.

The knee almost certainly hurts. That process of “feeling” the pain involves a fascinating interaction between the nervous system and the rest of your body.

The start of the “pain” begins with the cells of the nervous system, the neurons, that sense an outside stimulus. As the ground smashes into your knee, these neurons will feel that push and become electrically charged. This happens in response to touch, temperature, chemicals, and even vague internal organ pain.

Now, a sort of relay race will begin. The first sensory neuron will pass the message of, “Something hit us,” to the next neuron, which will pass the message to the next neuron. In this way, the message reaches your brain in a fraction of an instant.

Your brain is where the “feeling” of pain happens.

The brain analyses where the pain is located, what the cause is, and the intensity of the injury. The brain will then send signals to the body to address the pain… and this is where the gates come in.

The Gates In Your Spinal Cord

In the relay race from the body to the brain, there are broadly three types of neurons. They’re creatively named first-order, second order and third-order neurons. The first-order neurons receive the signal from the first pain receptor.

The first-order neuron passes it to the second-order neuron located in the spinal cord.

The second-order neuron passes the signal to the third-order neuron which delivers the message to the brain.

The neurons link to the brain via the spinal cord.

The gate theory of pain suggests that we are distracted away from “feeling” pain because of a fascinating interaction of neurons at the spinal cord.

There are three types of first-order neurons, divided into three categories.

Two types of neurons sense painful stimuli. They’re called A-δ fibers (pain from temperature) and C fibers (also sense temperature). A third fiber, called the A-β fibers, sense non-painful touch.

When you scrape your knee, the first-order neurons that specialize in detecting pain (A-δ and C) charge up and open the gate. This enables pain signals to be sent.

Now, let’s say you decide to rub your scraped knee or apply an icepack to the injured area. Congratulations! You just managed to close the gate.

By rubbing your knee or applying an icepack to the area, you manage to activate your A-β first-order neurons. This “intercepts” the painful stimuli signal and ‘closes’ the gate, preventing pain signals from being sent to the brain.

This ultimately explains why you forget about pain when you engage in another activity, such as rubbing your knee or applying an icepack.

Considering this theory, we’ve come up with a range of potential therapies to help those in pain.

For instance, two therapies known as the transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and Interferential current therapy utilize mild-electrical current at the site of pain to activate A-β fibers and thereby block painful signal transmission. Scientists are still testing how effective this treatment is, and how exactly it works.

Massaging the area that hurts may also be explained by the theory. Applying pressure could activate your A-β fibers and thus close the gate to whatever painful stimuli you may be feeling. Besides preventing pain signals from reaching the brain, a massage can also cause your brain to release chemicals known as endorphins.

Endorphins, Your Body’s Painkillers

Endorphins are your body’s natural painkillers. Your brain releases endorphins to decrease the intensity of the pain you feel.

They can decrease the pain you experience in two ways.

The first way involves the first-order neurons. Endorphins can cause your first-order neurons to release less of a substance, known as substance P, which can decrease pain signaling between your first- and second-order neurons.

The second mechanism by which endorphins help decrease your pain levels involves inhibiting painful signals from traveling along the postsynaptic or second-order neurons.

Intriguingly, according to research, singing, dancing and drumming can also trigger an endorphin release. That chemical release is accompanied by an elevation in post-activity pain tolerance.

Conclusion

Now you know the phenomena behind why you fan your hand after touching a hot stove, kiss a paper cut, or even ice a wasp bite. And next time you go for your vaccine shots, don’t forget to bring your headphones!

References (click to expand)

- Ropero Peláez, F. J., & Taniguchi, S. (2016). The Gate Theory of Pain Revisited: Modeling Different Pain Conditions with a Parsimonious Neurocomputational Model. Neural Plasticity. Hindawi Limited.

- Vance, C. G., Dailey, D. L., Rakel, B. A., & Sluka, K. A. (2014, May). Using TENS for pain control: the state of the evidence. Pain Management. Future Medicine Ltd.

- Adams, MHA, BSW, LMT, R., White, MS, LMT, B., & Beckett, PhD, RNC-OB, LCCE, C. (2010, March 17). The Effects of Massage Therapy on Pain Management in the Acute Care Setting. International Journal of Therapeutic Massage & Bodywork: Research, Education, & Practice. Massage Therapy Foundation.

- Bailey, L. M. (1986). Music therapy in pain management. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. Elsevier BV.

- https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003008.pub3

- Rampazo, É. P., & Liebano, R. E. (2022, January 17). Analgesic Effects of Interferential Current Therapy: A Narrative Review. Medicina. MDPI AG.

- Sprouse-Blum, A.S., Smith, G., Sugai, D.Y., & Parsa, F.D. (2010). Understanding endorphins and their importance in pain management. Hawaii medical journal, 69 3, 70-1 .

- Holz RW, Fisher SK. Synaptic Transmission. In: Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW, et al., editors. Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. 6th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK27911/

- Imamura, M., Furlan, A. D., Dryden, T., & Irvin, E. (2008, January). Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with massage. The Spine Journal. Elsevier BV.

- Dunbar, R. I. M., Kaskatis, K., MacDonald, I., & Barra, V. (2012, October 1). Performance of Music Elevates Pain Threshold and Positive Affect: Implications for the Evolutionary Function of Music. Evolutionary Psychology. SAGE Publications.